OR

Backtracking from federalism without a fallback will lead to another conflict

Published On: December 15, 2016 07:15 AM NPT By: Republica | @RepublicaNepal

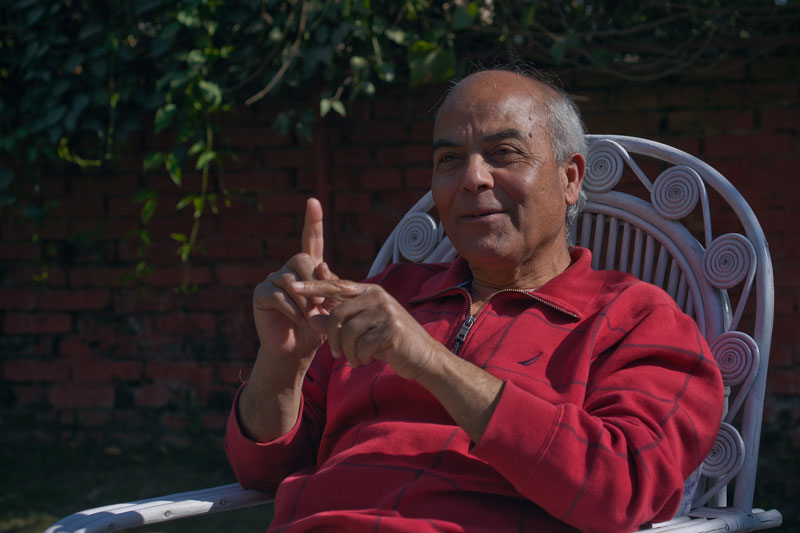

Bhojraj Pokharel as Chief Election Commissioner successfully conducted the first Constituent Assembly elections in 2008. The now retired civil servant has since closely studied other transitional countries and their electoral systems. He has at times even acted as an interlocutor in the (still ongoing) negotiations over the new constitution in Nepal. Are timely elections still possible? What can Nepal learn from other transitional countries? And what, in his view, are the dangers of putting off important decisions? Biswas Baral and Mahabir Paudyal caught up with him.

We have only 13 months to go for the constitutionally binding January, 2018 deadline for the three sets of elections. Are timely elections still possible?

If we had started election process right after constitution promulgation in September, 2015, all three elections could have been held within the stipulated time as we would have had over three years at hand. But more than a year passed without doing anything. Even today I don’t see tangible preparations for elections. So unless there is a magic I don’t see local, provincial and federal elections happening within the stipulated timeframe.

What are the factors that could impede timely elections?

Three factors are crucial for holding elections: political, legal and technical. Of this, political aspect is the most important. Unless there is a kind of understanding among political parties, legal and technical matters are really irrelevant.

Politically, we need to make constitution broadly acceptable by taking disgruntled forces into confidence and addressing their legitimate demands. Today, the constitution itself is contested. So first create conducive political climate. Next, we need more than a dozen electoral laws. Technically, we will have to reduce existing 240 electoral constituencies to 165. We have to create 330 constituencies for provincial assemblies apart from restructuring local bodies.

These are sensitive issues. Let me give you my own example. Prior to the first Constituent Assembly election, we had agreed to continue with the existing 205 constituencies. Later the number of constituencies was increased to 240 and we needed immediate restructuring of the constituencies. Constituency delimitation commission was duly formed. But its report was contested and those who did not agree with its recommendations obstructed the parliament for 19 consecutive days. Only when the parties agreed to review the report and amend the constitution to that effect, was the dispute resolved and the election process went ahead.

Only when legal, political and technical issues of election are resolved can Election Commission start preparations. It needs at least 120 days for this. If the parties can unbundle these complications and come to the same page, three elections are possible within January, 2018. We can hold local elections in June, 2016 and election of provincial assemblies and national parliament by December next year.

You once suggested that three elections could be held together. Is that a feasible option?

Three elections can be held separately as well. But there is risk. Every political party wants to win. But only one party does. The losing parties will have no incentive to face the polls immediately and it might then start weaving strategies to defer other elections. This will unnecessarily delay other elections. This is why I said the option of holding three elections simultaneously should be open.

We should also mention election dates in the constitution itself so that political parties don’t find excuses to delay elections. So long as election dates are not included in the constitution there will be no political stability in Nepal.

All elections have to be held within a year from now if we are not to miss constitutional deadline. It is not easy to hold three elections at once. But we can at least explore the possibility. If it is not possible, we can hold local polls in June and both provincial and federal parliament elections in December, 2017. These are not normal times. We are in a crisis and should act accordingly.

Major parties have reportedly agreed to hold local polls as per transitional provisions of the constitution. Was this a wise option?

One year ago, these parties were of the view that as it could take the local body restructuring commission long to complete its job, we should hold local elections for an interim period. But they could not forge broad understanding for this. If they had, we could have had local elections a year ago, comfortably. Today, these parties have made a volte-face. They are talking about holding elections for existing local institutions. The danger is that it may set a bad precedent. What if tomorrow they say, ‘We could not resolve federal complications, so let us hold parliamentary election as per the old provisions?’ This could ultimately make the constitution an irrelevant document.

The question before the parties is if they want to make this constitution redundant. Even if the parties opt for elections of existing local institutions, these institutions will exist for an interim period. Thus this does not solve the problem in the long run.

Assuming that the elections can be held on time and under the status quo, what kind of complications will they result in?

If all political forces agree on elections, it will create a kind of environment that will help bring politics back on track. The political parties that have contested elections will be morally bound to accept the results. Thus the situation would be a lot better than the state of political void we now find ourselves in. But even for this, there has to be an atmosphere whereby the political forces enthusiastically participate in elections.

What in your view is the main hindrance to viable long-term settlements?

In a way Nepal is a minefield of diversities and sensitivities. Our issues are diverse and we have different way of perceiving and understanding our political problems. There is a fundamental difference in how one set of people understand these problems with the way another set understand them. Unless we can somehow reconcile these differing views, the political deadlock is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

But how is this possible when people, for example, have started arguing whether the country needs federalism or not?

Yes, there are debates over whether the decision to go for a federal model was a mistake.

But there is another side to it as well. A large section of the people believes only federal system can guarantee their rights. Issues of culture, identity and language are attached with the federal system. Another powerful section of the population believes that this country is an integrated whole comprising mountains, hills and plains and this should remain intact even in federal provinces. They believe that once mountain-hill-plain interdependence is broken it could lead to national disintegration.

But the other group has been saying that this interdependence does not do justice to their language, identity and culture which are different from language, culture and identity of hill and mountains. So there is a fundamental difference in understanding of federalism between Pahad-origin population and Tarai-origin population. The current deadlock is the result of the failure of two groups to come to a meeting point.

But how can this elusive meeting point be found?

Each group needs to understand the sensitivity of the other group. They need to get into the depth of the issues raised by each other. Then there should be meaningful dialogue between the two groups. Today, they meet informally, exchange greetings, have tea.

There is no record or minute of what they have talked about. These meetings have to be more structured.

What do you say to those who say federalism should be put on hold for the moment?

What will you say to the large section of population which believes federal system is the only way they can get their culture, language and identity recognized and the only way to ensure their wellbeing? If the parties come with a formula to address the aspirations of this population and only then backtrack from federalism, then perhaps it will be acceptable to both the sides. But backtracking from federalism without a credible fallback option will lead to another conflict.

You have been a first-hand witness of political processes of many transitional countries. What can Nepal learn from their experiences?

No governance system is completely right or wrong. So long as citizens of a country feel that they are safe, and state has done them justice, they will agree to be governed under any kind of political system. There is stability in the developed countries because people there feel their governments ensure their wellbeing. They trust their institutions and political leaders. Perception matters a lot in politics. In countries where citizens do not trust their institutions and leaders, even a minor event can spark dissatisfaction. As for whether unitary or federalism system is better, the important thing is again that the state is seen doing justice to all its citizens, whatever their regional, cultural or religious affiliations. In a homogenous society, there is no aspiration for a federal system. But not so in a heterogonous society.

A lot rests on the capability of political leaders. Take Sudan. South Sudanese voted to create a new country in 2011. Today, that young country faces an existential threat and people are regretting that decision because the leadership failed to adequately address their aspirations.

You have also been in constant touch with Madheshi leaders. What do they say? How ready do you find them for a compromise?

There is a realization among Madheshi leaders that a political solution is necessary.

Madheshi leaders have the feeling that Kathmandu deliberately overlooks their concerns.

Their concern is that Kathmandu flatly labels them ‘anti-nationalist’ when they raise voice for their rights. They are hurt that a section of the political class always questions their loyalty to Nepal. Their other concern is the rise of extremist forces in Tarai.

They worry that the failure to address their grievances within the constitutional framework may ultimately take Madhesh out of their grip. They are clear about it. Sometimes they are accused of encouraging secessionist tendencies but I have not met a single Madheshi leader who believes in secession. Sometime they say in jest, ‘We have lived a dignified life in Nepal. Who knows what will happen when we secede.’

Kathmandu must not cast aspersions on citizens of Madhesh. We have created a situation in which a person feels more nationalist because he comes from one region and another person has to feel demoralized because he comes from another culture or region.

This tendency only widens the differences between the populations of two regions. And it could lead to ethnic and regional conflict. Our speech, action and behavior should be aimed at forestalling that eventuality.

We should not leave any space for another conflict because more you defer the crisis, the more intense it will become.

Current negotiations have become more complicated compared to negotiations before the constitution promulgation. If we put it off again, things will get even more complicated.

Deferring the crisis is no solution. If the current leadership fails to address the pressing issues, it will do great injustice to the country and to our posterity. Political leaders should not take comfort in this dangerous bet.

You May Like This

CM Rai's question: Can the gun be placed on my shoulders for the failure to name the province?

KATHMANDU, August 23: The (CM) of Province 1, Rajendra Kumar Rai, has alleged that development has become dictatorial after the... Read More...

Low budget spending disappoints expectations under federalism

KATHMANDU, March 23: Disappointing voters who expected rapid and meaningful development following the restructuring of the country, the provincial governments... Read More...

Federalism is at risk as only center holds authority to enact new law throughout country: Bimal Koirala

Nepal is exercising the federalism after the conclusion of the three-level elections- local, provincial and federal parliamentary. A lot of... Read More...

Just In

- Light rainfall likely in hilly areas of Koshi, Bagmati, Gandaki and Karnali provinces

- Customs revenue collection surpasses target at Tatopani border, Falls behind at Rasuwagadhi border in Q3

- Rain shocks: On the monsoon in 2024

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

Leave A Comment