OR

Nepal Army: All eyes on profits

Published On: December 19, 2016 12:20 PM NPT By: Rudra Pangeni | @rudrapang

The security body entrusted with protecting the nation is overstepping its constitutional mandate, increasingly turning into a profit-making enterprise.

KATHMANDU, Dec 19: The estimated cost for the Devsthal-Kainadanda section of Jajarkot-Dunai road was Rs 195.4 million. The actual project cost exceeded this by Rs 88.42 million, without sufficient technical clarifications.

Procurements exceeding Rs 100 million were made in the year 2015 without following proper procedures as stipulated by Article 7 of the Public Procurement Act, 2007.

The medical college hospital run under the Army Welfare Trust has 491 beds, which, according to Nepal Medical Council (NMC) criteria, allows only 82 students to be enrolled in the medical college. But the college has been enrolling 130 students, which is against the NMC guideline of six patient beds for each MBBS student. This compromises the quality of medical education, turning out students without the needed hands-on experience.

A purchase agreement of Rs 225.1 million was entered into as per Article 27 (1) of the Procurement Act 2007. However, the estimated cost was exceeded by Rs 15.6 million.

The above remarks quoted from the Auditor General’s annual reports from 2013 to 2015, may appear to be about a public department or enterprise. But these are questions raised by the Auditor General’s office over institutions run by the Nepal Army. Reports from the government’s regulatory body before 2013 also contain similar remarks on the financial dealings of the Army, indicating that an institution charged with responsibility for defending the nation seems more inclined toward profit-making.

Of late, the Army’s interest in making financial gains seems to have grown in unusual fashion. It is clearly taking full advantage of the country’s prolonged transition and the constitutional loopholes. Such strong remarks coming from the Auditor General’s office with regard to public spending would usually come under the scanner of the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority.

But when it comes to the Army, there is no provision for oversight, which raises an even bigger question about the government’s decision to hand over big projects to this security body, with little rationalisation and bypassing public departments that are technically and logistically equipped to carry out development work.

The Army is now involved in several development projects, including the Kathmandu-Tarai Fast-track Road and the construction of an International Airport in Sindhuli. It is also spreading its enterprises to medical education, and this by overstepping the criteria. And of late, it has entered the real estate market, in addition to running its own gas stations and financing projects out of its welfare trust funds.

They don’t give a damn

The Army is involved in several other road construction projects, including Jajarkot-Dolpa, Kali Gandaki Corridor, Karnali Corridor and Rasuwa’s Mailung-Syafrubesi.

According to the Auditor General’s annual report, the Army spent Rs 1.55 billion in fiscal year 2015/2016 constructing a 151-kilometer stretch. They are now opening 1,200 kilometers of road track under 22 different projects.

Army spokesperson Brigadier Tara Bahadur Karki defends the Army’s work, saying, “The Army is simply working on government-assigned duties; these are challenging and risky projects that only the Army can undertake.”

This narrative of the Army contributing to the country’s development by undertaking challenging and risky jobs sounds convincing. But our investigation shows that its role is nothing more than that of a rent-seeking contractor that is skimming profits, rarely using its own manpower or equippment and mostly sub-contracting to professional contractors of its choosing.

Contractor Mahesh Kumar Bhujel, who provided manpower to the Army for work on the Syafrubesi-Mailung road, says, “I know Major Sanjay KC and Brigadier Uddhab Bista at the development directorate, and was requested by them to work on the project.” Bhujel has been supplying manpower for the Army’s projects for the last 13 years, working in several districts, including Kalikot, Mustang and Sindhupalchowk.

Usually, labourers working to open the tracks for road construction get paid wages on the basis of a full day’s work, which is usually 1.25 cubic meters. Normally, the minimum wage is Rs 395 per day, but it could go as high as Rs 800 depending on the remoteness of the project site. Similarly, the Divisional Road Office in Kathmandu has set a rate of roughly Rs 100 per cubic meter for soft soil dug by excavator.

“Using the machines certainly cuts the labor costs significantly, but there is no way to verify whether the project has been using excavators or more expensive human labor as shown on paper,” says an official at the Attorney General’s office. The official admits there are millions to be made through this difference while opening tracks for a single road project.

The Auditor General’s office has repeatedly pointed out that the Army has been violating the Procurement Act in its development projects as well as in its internal construction work.

In fiscal year 2012/2013, the Army was given the job of opening the Ridi-Rudrabeni Argali track, for which Rs 20 million was disbursed in January 2013. The same fiscal year, the government doled out another Rs 138 million to the Army in six installments for the same project. The sixth installment of Rs 32.5 million was disbursed on 9 July, 2013, only four days before the end of the fiscal year. But even this amount was completely spent, which is unusual.

The Procurement Act requires the submission of a project completion report after the completion of the construction work. But the Army has not presented reports on any of its construction projects. “In the last three years, we have repeatedly asked the Army to prepare the project completion reports.

But they simply ignore us.” says Baburam Gautam, spokesperson at the Auditor General’s office.

“We have been carrying out all our work as per the law. If some of the reports are missing, we will submit them soon,” said Army spokesperson Karki. According to the Auditor General’s report for 2015, the Army has spent Rs 135 million for the construction of an epicenter building and another 680 million for building a veterans hospital without prior approval for either project or the budget.

A close look at Army spending on provisions also reveals plenty of inconsistencies. The Auditor General’s report of 2014 takes serious note of the fact that the Army approved a higher bid of Rs 13.76 per packet against another bid of Rs 11 per packet for the same biscuits, with the total surplus spending amounting to Rs 95.81 million. In milk supplies also, the Army was found to have given a contract of Rs 64.71 million to the higher bidder. “According to Procurement Law, it is illegal to spend public money without following proper procedure,” concludes Naresh Chapagain, spokesperson at the Public Procurement Monitoring Office.

International experience shows that while it is not unusual to use the Army for projects deemed of national importance, the projects themselves are supervised by civilian bodies, except in the case of defense projects. That is not the case in Nepal, where the Army takes over development projects and spends with zero transparency.

Former Defense Secretary Ishwari Prasad Paudyal says the main reason for this lack of unaccountability in the Army is the small size and weak structure of the Defense Ministry, which has rarely been a priority for the political parties. The Nepal government, which has about 80,000 personnel, is managed by the Ministry of General Administration with around 150 staff. But, the Defense Ministry which has to manage a 96,000-strong force is staffed by only 50. “Even those assigned to the Defense Ministry routinely ask for transfers due to the difficult working conditions there, “ says Paudyal.

Eyes on profit

In the last few years, the Army has steadily increased its investments in medical education, a sector which has attracted many private investors. The Army already runs a College of Polytechnic and College of Dental Surgery. It has also been running a College of Medicine and a College of Nursing under its Institute of Health Sciences. The Army’s Civil Hospital is also under construction.

Although the Army has set aside a 10 percent scholarship quota in its MBBS program for the Ministry of Education, and a 15 percent quota for the families of those in Army service, the cost of the MBBS at the Army’s medical college is high for members of the general public.

The cost for the MBBS is Rs 3.6 million for regular students and Rs 3.3 million for Army families, which isn’t very different from private medical colleges. Even within the 45 seats set aside for the children of retired and serving Army personnel, the MBBS cost varies for different ranks, with a free of cost provision for the children of those who died or became disabled during service.

However, the Auditor General’s report states that the Army has openly violated NMC criteria while enrolling students. The Army hospital has 491 beds, which allows only 82 students as per the NMC criteria of six patient beds per student at the teaching hospital. But the Army has admitted 130 students.

Also, by charging students more than Rs 3.65 million for the MBBS course, a figure which the government agreed to after Dr. Govinda KC’s repeated hunger strikes, and by enrolling an additional 48 students against the guidelines, the Army has raked in Rs 170 million in profit. This contradicts the supposed vision of the Nepal Army Institute of Health Sciences as a ‘not for profit’ organisation. Security expert and author of Military and Democracy in Nepal, Indra Adhikari says, ‘There isn’t much difference between the privately run and Army run medical colleges. It’s clear they have their eyes on profit.’

“We have the capacity to enroll 150 medical students. We have admitted 115 students this year. We have been admitting students as per the terms and conditions of the Institute of Medicine. Moreover, Parliament’s state affairs sub-committee visited the hospital and they told us it is all as per the law,” said Army spokesperson Karki.

Recently, the Army submitted details of its land transactions to the Auditor General’s office, stating that it has bought several plots of land in Chitwan and Kathmandu worth Rs 525.5 million. The money was paid out of the Army Welfare Trust. “There are no further details on the land or the estimated cost of constructions on it,” informed a source at the Auditor General’s office. “When we inquired how much land and fixed assets there were under the Welfare Trust, spokesperson Karki told us no such records existed.”

The Army has been significantly increasing its investments in real estate, citing it’s objective of providing land and homes to in-service and retired personnel at affordable rates.

But the heydays for the Army seem to have only just begun. Karki said the Army has invested in a bottled mineral water plant in Sundarijal. Although, the stated purpose for investing in a bottling plant is for self-consumption, Karki admitted that the company would supply water commercially in future.

One of the first things Energy Minister Janardan Sharma did after assuming office was making a call to CoAS Rajendra Chhetri and proposing that the Army invest in large hydropower projects. An elated

Army is now making internal preparations to remove the legal obstacles for the Army to invest in hydropower.

The government’s decision to hand over development projects to the Army has been criticized from various quarters, including by security experts. But Army spokesperson Karki accuses private banks of fueling rumours. He said, “Some banks are worried that the Army’s investment plans in hydropower will hurt their business and are spreading rumours. Our welfare trust has so far been running only on bank interest and the earnings from UN peacekeeping missions. We now need to think of alternatives like investing in hydropower to make the work of the welfare trust more sustainable. This has nothing to do with profit-making.”

However, security expert Indra Adhikari reckons, “ The Army’s increased inclination towards commercial ventures using the welfare trust money is against the vision with which the trust was established.”

Trust and distrust

During a press conference in September, the Army had informed that the Army Welfare Trust had Rs 33.67 billion in savings, and that the main source of income came from the interest it generates from various banks. In Fiscal Year 2015/2016, the Army earned Rs 1.49 billion in interest and paid Rs 223.8 million in taxes. This means that the average interest rate the Army receives on its bank savings is only 4 percent, which is almost half the current market rate. This raises serious questions about the decision-making of high ranking officials, and leaves plenty of room for speculation as to why the Army settled for such a low interest rate on its welfare funds.

This is against the lofty claims by former CoAS Chhatraman Singh Gurung about increasing the trust funds significantly with ‘high’ interest rates between July 2009 and 25 June, 2012. During this period the welfare trust grew from Rs 13.52 billion to 22.74 billion. This was a period when trust savings in ‘A’ category banks had increased from 81.9 percent in 2009 to 96.6 percent in 2012. Details of this can be found in the Nepal Army’s publication, History of Nepal Army, published towards the end of Gurung’s tenure in 2012.

Between 2009 and 2012, the trust funds increased by 68 percent from Rs 13 billion to 22.74 billion. But surprisingly, four years since then, the amount only increased by 48 percent to 33.67 billion. The main reason for this change is the bank interest rates. When asked for details, spokesperson Karki said the names of the banks where the trust has its money can be shared, but the interest rate it receives cannot be disclosed. “It should be beyond doubt that an institution like ours does not negotiate on interest rates.”

Building nation while its own languish in bunkers

At the peak of the Maoist armed conflict in 2001, the Army’s strength was 45,000. Gradually, the number increased and now it stands at 96,600. The UK, which is one of the world’s leading powers, has reduced its infantry size to 95,000 to invest more in its citizens’ welfare programs. There are several other countries which are also cutting down on their military and defense spending. In this context, it is an important question to ask in the public interest- does an under-developed country of Nepal’s size requires such a large army? Why can’t the Army be modernized and equipped to keep it at a manageable size?

What is also interesting is, despite its significant increase in numbers, the rank structure hasn’t been changed to reflect this increase. There aren’t enough higher ranks to accommodate the increasing rank and file. As a result, many of them, on whom the state spends hundreds of thousands, end up retiring at mid-career ranks like major and colonel.

The Army’s weaponry, vehicles and other resources are also outdated and insufficient. But the issue of restructuring and modernizing hardly receives priority in security debate and planning.

Until 2007/2008, housing infrastructure was available only for 49 percent of personnel. This increased to 80 percent in 2011/2012.The Army added these infrastructures under its campaign

‘From Bunkers to Barracks’. But after the devastating earthquake of 2015, many of these were damaged and the campaign couldn’t achieve its target. According to spokesperson Karki, 35 percent of personnel are still living in bunkers.

Despite these urgent needs for investing in reforms within the institution, the Army leadership seems more inclined towards profitable business. “These trends are alarming and point toward the danger of the Army moving toward the Pakistani model,” says Prof Dhruva Kumar, a noted security expert. “The Army is not a government entity like the National Trading Corporation. Its primary duty is safeguarding the nation and not running after profits. If the Army is allowed to expand into commercial enterprise, it will soon create pressure in the private sector as well,” concludes Prof Kumar.

Security expert Adhikari expresses similar concerns about the Army’s corporate inclinations. “Defense is a service in the interest of the nation, and must not be turned into a profit-making enterprise. The armies in democratic countries are never allowed to be directly involved in buying and selling.”

(This report was prepared by the Centre for Investigative Journalism)

You May Like This

Chief of Indian Army to mark his presence in Nepal Army Day

KATHMANDU, Feb 12: The Chief of Indian Army, Bipin Rawat is coming to Nepal on the occasion of Nepal’s Army... Read More...

SCOPE Nepal provides foil blankets to Nepal Army

KATHMANDU, Jan: SCOPE Nepal, an NGO working in peace, security, environment and social justice, handed over 378 emergency foil blankets to... Read More...

Joint training between Nepal Army and U.S. Army

KATHMANDU, Oct 17: A joint training between the Nepal Army (NA) personnel from Shree Mahabir Ranger and the military personnel... Read More...

Just In

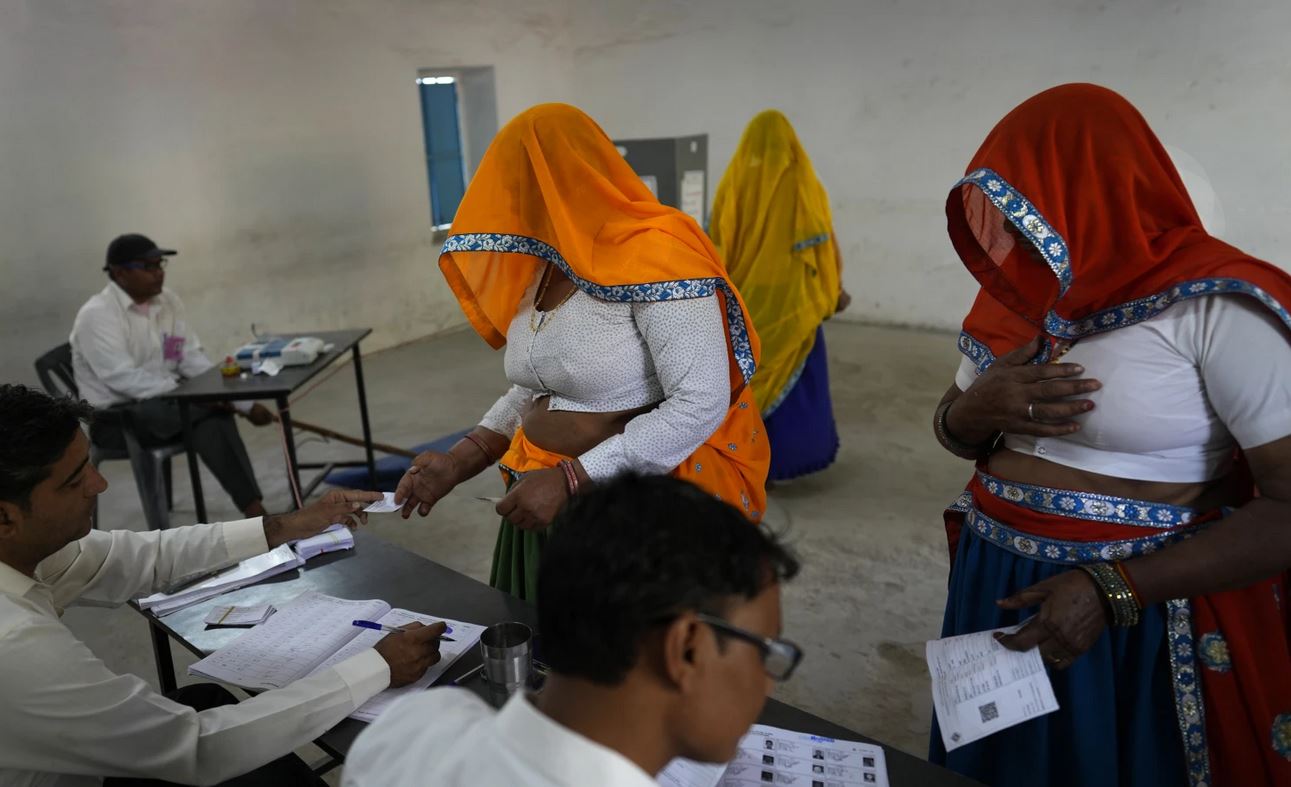

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment