OR

Much of our debate is focused on whether to dismantle or retain five development-regions set up in federal model

I have heard professionals and politically aware people alike from hills, mountains and Tarai say this: Why don’t leaders turn five development regions into federal provinces? Why don’t they revise federal demarcation in line with north-south alignment? Many a times, I have heard them say this is the best possible solution.

This view strongly resonates within Nepali Congress, CPN-UML and even Maoist Center. UML chief K P Oli has publicly appealed to return to five development region model. Congress leaders like Shekhar Koirala and Sashank Koirala have been saying this all along. Another Congress leader Ram Sharan Mahat disclosed with us last week that late Girija Prasad Koirala, whose government had signed an agreement with Madheshi forces in 2007 to federalize the country, was strongly in favor of north-south alignment.

During opinion collection on draft constitution, majority of people had demanded delineating provinces along north-south lines or to turn five development regions into five provinces.

So what do you make out of this fascination for north-south alignment?

A section of intelligentsia flatly dismisses this question. For them, those who keep such fascination are ignorant, unaware of intricacy and spirit of federal government system and are guided by prejudice of suppressing weaker and marginalized communities by the dominant majorities. Those who believe in north-south alignment are pitied, and at times even ridiculed for lacking reason and foresight. Or they are immediately called followers of king Mahendra. In this interpretation, this model is bad because it bears the imprint of the Panchayat system.

There is a streak of self-aggrandizing attitude in this reading: That people cannot think for themselves, they do not know what is right and therefore we have the burden to tell them what is best for them. While this reasoning may not be downright irrelevant, it is undemocratic. You cannot reject and undermine a dominant view in a democracy.

At a time when there is a rush to dismantle everything of Panchayat days in the name of progressivism, discussion on this ‘old idea’ might sound like a sacrilege, but it is never too late to examine the rationale, if any, of the idea that almost every political leader admit is right in private conservations with journalists but do not dare to mention publicly for the fear of being perceived ‘politically incorrect.’

District, zone and development region as administrative units does not have a long history in Nepal.

Historical records show Rana Prime Minister Bir Shamsher had divided the country into 32 districts—20 in the hills and 12 in Tarai plains. The number reached 38 by 1960 and then to 75 when King Mahendra restructured Nepal’s village and town units, districts and zones. When Mahendra created administrative infrastructures in each district and delegated officials, practice of administrative decentralization actually started. From the late 60s, preparation had started, in consultation with the best brains of the time, to develop larger regional units to integrate the country economically and geographically.

When in 1972, King Birendra created 4 development regions, later five (with addition of Far-west region in the late 70s), it marked the first exercise of regional development concept in Nepal.

The idea was to promote ‘national unity’ by minimizing regional imbalances and by utilizing the natural resources of the mountains, hills and Tarai. Regional headquarters were set up in all regions to oversee and monitor the development works. The goal was to tie in the economy of the plains with the hills and vice-versa.

Often development region model is seen as a tool to perpetuate and consolidate powers by Kathmandu. Development was a cover to hide this goal, the argument goes.

However, Bhekh Bahadur Thapa, Nepal’s senior foreign policy hand who was also a member of the team tasked to restructure administrative districts in the early 60s, does not see it that way. “There was no political motive in this. Idea was to increase interdependence and proximity of hills, mountains and plains, a landmark move of national integration,” he told me recently.

The 14 administrative zones, with each headed by a zone commissioner, a royal appointee, whose primary duty was to work for the palace than people, got scrapped after 1990’s political change. Zones are no more the defining feature of our administrative system. The concept of districts and development regions still remains.

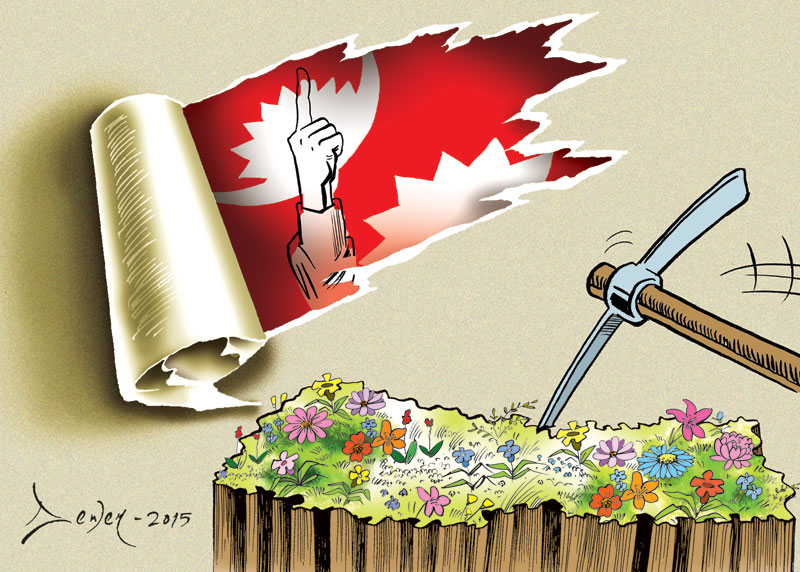

But this framework that defined Nepal’s decentralized administrative and development system for about 50 years is at the core of federal debate. Much of our federal debate is focused on whether to dismantle or retain this structure while adopting federal model that has generated so much fear and anxiety before its implementation.

Was the five development region concept a total failure? Can it be made a baseline structure to resolve federal contentions? I asked eminent political scientist Hari Sharma. “Not that five development region model was flawless,” he said. “It was used more for facilitating visits of kings.

Development received low priority.” It has been made to seem like an irrelevant idea because “we never talked about integration of identity with ecology in federal system, which is at the core of five development region concept.” Sharma thinks it can be taken as a baseline structure. “If we are talking about giving political and cultural representation to the country as a whole, why cannot we do so within the existing regions as well? But we never gave a serious thought to it.”

“Five development regions can be transformed into political units to accommodate people’s political aspirations,” he explained. “People feel comfortable with five development regions because unknown evil looks more threatening than known evil.”

Madheshi and Janajati lobby, however, argues that this Mahendra model does not address aspiration of identity and inclusion and, therefore, must be ruptured. Consider their argument in favor of separating hill districts from Province 5. Ruling and Madheshi parties would have us believe protest in Province 5 is instigated by CPN-UML. Only partly true. Dissent against dividing hills and plains is actually the outcome of entrenched hill-plain integration and coexistence built through cross flow of people over the years.

Needless to say, there were inadequacies with five development regions. In 2005, Harka Gurung, the chief architect of five development regions, had recommended reforms. In “Nepal Strategy for Regional Development” report, Gurung had proposed, among other things, integration of highland and lowland economies based on product specialization, extension of Tibet Autonomous Region connection for development of remote mountain areas, creating industrial complex at major road junctions along the East-West Highway for large-scale industries, affirmative action for indigenous people, Dalit and other disadvantaged groups in education and employment and establishing Regional Development Council in each region for coordination of development activities. Gurung died in helicopter crash in 2006, the country went on federal path in 2007. The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

In a country where politics has not become more than a tool to secure immediate gains and protect one’s constituencies for upcoming elections and where political actors don’t look beyond 10 years, we should not be carried away by their rhetoric.

Sher Bahadur Deuba, active campaigner of ‘undivided’ Far-west, is chiding UML for refusing to ‘divide’ the Mid-west. Madheshi Morcha, whose leaders threaten of secession now and then, is blaming UML of trying to ‘disintegrate’ the country. Parties keep changing positions. With one apology they impress on the people that they have corrected their mistakes. But UML’s current stand that hill-plain interdependence must be at the core of province demarcation is right and just.

Narrative of division has been foisted on us for the last few years. Impression has been created that provinces cannot be demarcated in line with north-south alignment and that hills and plains cannot come within a same province.

In his 1924 novel, A Passage to India, EM Forster presents dilemma of whether the colonized Indians and colonizer British can become friends. Story is set in colonial India. Since impression has been created that hill people are colonizers and Madheshis the colonized, let me cite the conversation between Cyril Fielding and Doctor Aziz, two main characters. Fielding asks Aziz to forget all bitterness and become friends. ““Why can’t we be friends now?”” asks Fielding, ““It’s what I want. It’s what you want.””

“But the horses didn’t want it…the earth didn’t want it…the temples, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds…they didn’t want it, they said in their hundred voices, “No, not yet,” and the sky said, “No, not there.””

If you advocate coexistence of hills and plains, you might be told the hills don’t want it, neither the plains. Or that people of hills and plains can become friends only if they are separated by provincial demarcation. We have had enough of this narrative. This deceptive narrative should be countered.

mahabirpaydyal@gmail.com

You May Like This

Ex-King Gyanendra: Parties weakening mountains-hills-tarai bonds of unity

KATHMANDU, Dec 22: Expressing concern over political instability and anarchy prevailing in the country, former king Gyanendra Shah has said... Read More...

Party unity only after elections: MC Chairman Dahal

RATNANAGAR, Nov 13: Chairman of the CPN (Maoist Center), Pushpa Kamal Dahal, has said it was a baseless rumour that the... Read More...

All party unity must for elections: Peace Minister

KATHMANDU, Sept 18: Minister for Peace and Reconstruction Sitadevi Yadav has stressed on all party unity to hold all three... Read More...

Just In

- Save the Children report highlights severe impact of air pollution on children

- NATO Serving as a Catalyst to Fuel Violence

- Home Minister denies any delay in providing relief to wildfire and fire victims

- Ties with Tehran

- CM Kandel requests Finance Minister Pun to put Karnali province in priority in upcoming budget

- Australia reduces TR visa age limit and duration as it implements stricter regulations for foreign students

- Govt aims to surpass Rs 10 trillion GDP mark in next five years

- Govt appoints 77 Liaison Officers for mountain climbing management for spring season

Leave A Comment