OR

Here’s hoping the likes of Motiram Bhatta and Kamal Mani Dixit flourish, even in hard times like these

Kushe Aunsi, 2072. At Lekhnath Sadan, near Thamel, the who’s who of Nepali literary firmament had descended. Yours truly was the only ‘nobody’ present at the event, perhaps.

So it was only natural that many piercing eyes, with their questions, zoomed in on me as if to ask: Who are you? And why are you here?

No, I was not at that august gathering to sip free tea and feast on munchies. I was there because I had to be there. Why? Because my father Srikrishna Gautam was a literary, scholarly figure. I had to be there because he was no more, physically.

In Nepal, this not-so-glorious tradition has taken root. Government entities like Radio Nepal and Nepal Academy are its staunch adherents. In keeping with it, Radio Nepal does not bother about the condition of musicians, singers and lyricists whose songs it runs. Why would it? After all, it has more important things to cover like never-ending development works, the fall of a government and the installation of another one, so on and so forth. It has to cover things like ribbon-cutting ceremonies featuring ministers. Its bosses have more important things to do, things like saving their jobs in times of never-ending political uncertainties.

But the day a musician/singer/lyricist passes away, the state-run radio, it appears, finds itself in a huge ocean of grief. On that day, the radio pays rich tributes to the musician/singer/lyricist by playing stuffs that he/she is associated with, more often than on other days (Is it also because the radio does not have to pay royalty to the deceased? Yours truly knows not). On that day, there are interviews to take, tears to shed and grief to overcome. After playing those songs, shedding those tears and broadcasting those fond memories, the radio somehow overcomes the overwhelming grief. Until another such death, it’s business as usual for the state-run radio.

Nepal Academy also performs a standard procedure when a ‘noted’ scholar/writer dies. Men and women of letters get rich tributes if they happen to be close to ruling political parties. Tributes flow in for the ‘noted’ ones (those close to centers of power, of course), whose bodies are kept on academy premises till late in the afternoon to enable people to pay their last respects. In some cases, even ministers turn up to shed crocodile’s tears on the flower-decked, Ramnami-clad or party flag-covered bodies of the departed….

In the eyes of the academy, ‘minor’ literary figures do not count, so their death is unimportant. Is it because we have a higher number of litterateurs/scholars per capita than any ‘civilised’ country in the world? The academy knows better.

Back to Lekhnath Sadan and why I landed there on that cold September afternoon.

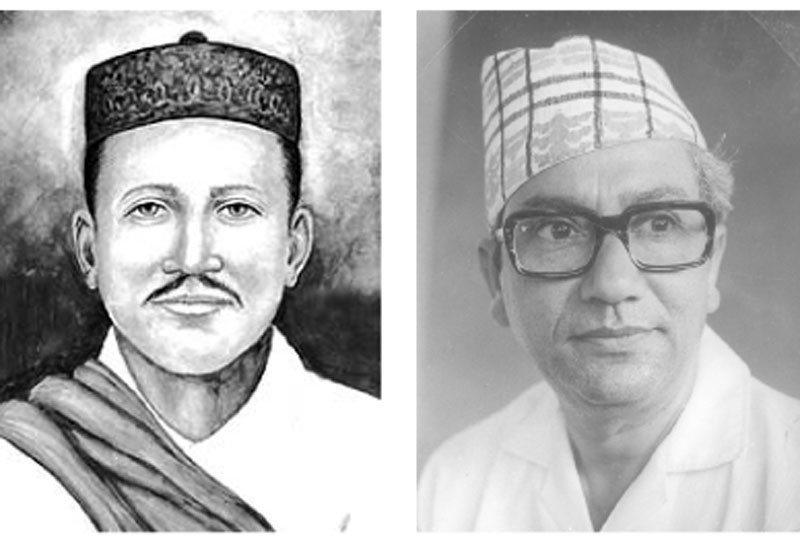

A few days before Kushe Aunsi of 2072, I got a call from some Sadan official. As per the Sadan ritual, I was supposed to give them a framed photo of my papa, who had died a few months ago, to enable them to offer floral tributes to him on the day of Kushe Aunsi, the day the celebrated Motiram Bhatta, who brought to light the works of Bhanubhakta Acharya and made him famous, was born.

So I went there at the Sadan hall glittering with Nepal’s noted literary figures, both young and old. Among the old was noted scholar Kamal Mani Dixit, who was the center of attraction.

Why wouldn’t he be? After all, who else among Nepal’s literary figures enjoys such good health (and wealth too) in their 80’s? Who else can boast of presiding over resourceful institutions like Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya, Jagdamba Press and Madan Puraskar, also known as Nepal’s Noble Prize, to who’s who of Nepali literature, and of publishing Nepali, a famous Nepali language periodical? And who else can brag about sharing his birthday with Motiram?

Like Motiram, Dixit made a huge contribution to Nepali literature. In one aspect, Dixit was luckier than Motiram. Motiram died young, whereas Dixit passed away when he was in his 80’s.

In Nepali society, there’s a popular belief that Laxmi, goddess of wealth, and Saraswati, goddess of knowledge, are enemies. This means the two goddesses take each other’s disciples as enemies. Laxmi has no sympathy for disciples of Saraswati—scholars, writers—and vice-versa, so goes the belief.

The belief does not appear to be unfounded in our context. The great poet Laxmi Prasad Devkota is a vivid example. Call it an irony: Though he was born on Laxmi Puja, the day of Goddess Laxmi, economic insecurities dogged him all his life. Amid these hardships, Goddess Saraswati seems to have blessed him as his famous works like Muna Madan, Bhikhari and Shakuntal show. For Bhairav Aryal and many other literary figures, economic insecurities were part and parcel of everyday life.

Often, we read that writers abroad make fortunes, that many have their their own estates and that royalties from their works ensure them a good life even when they have stopped writing. In our country, however, most of the writers, except those close to corridors of power, continue to face an existential crisis.

For many aspiring pen-smiths, publishing their works in dailies, monthlies and weeklies is, oftentimes, an insurmountable ordeal. Many pieces coming from them land straight into the dustbin because they are not members of ‘newspaper and magazine fan clubs’, because editors do not know them.

Even in this grim scenario, we get to read newspapers extol the virtue of press freedom and freedom of expression!

In our society, many important, talented people have many other things to do, so they don’t get the time to write. When they become larger than life figures, they can hire ghostwriters. That’s a win-win for both the writers and the rich and the famous. What say you, readers?

Back to the Laxmi-Saraswati conflict. Even in this grim scenario, there have been a few people, who have received ‘blessings’ from both Laxmi and Saraswati. Dixit was one of them.

Wrapping up this piece, here’s hoping that the tribe of Kamal Mani Dixit and Motiram Bhatta will flourish, even in hard times like these. And here’s hoping that the ‘tradition’ of remembering literati only on Kushe Aunsi ends, sooner than later.

The author is a Kathmandu-based journalist

You May Like This

Isolated tribe members in Brazil spotted in drone footage

PERU, Aug 24: In the sprawling greenery of the Brazilian Amazon, near the border with Peru, a group of people... Read More...

Just In

- Special session of Koshi Province Assembly begins

- Lumbini Province: Three UML, one NUP leaders to take oath as ministers without portfolio today

- Unified Socialist’s general convention from June 30

- Former Indian Foreign Secy Shringla highlights India's strategic engagement with neighboring Nepal

- iPhone 14 Pro Max-shot Nepali film 'A Place Under the Sun' set for global OTT platform release

- Vitamin A being administered to children across Nepal

- Idols of Lord Ram and Sita consecrated at Nepali temple in Thailand

- Satdobato-Balkumari road section to be closed at night for several days

Leave A Comment