OR

On June 24, Dolakha became the 29th district in the list of districts that have so far been declared ‘literate’ across Nepal. Amidst a program that included rallies involving school children, government representatives, members of political parties and civil societies, I/NGO staffs and representatives from UN agencies, the declaration event brought enthusiasm and excitement among its participants.

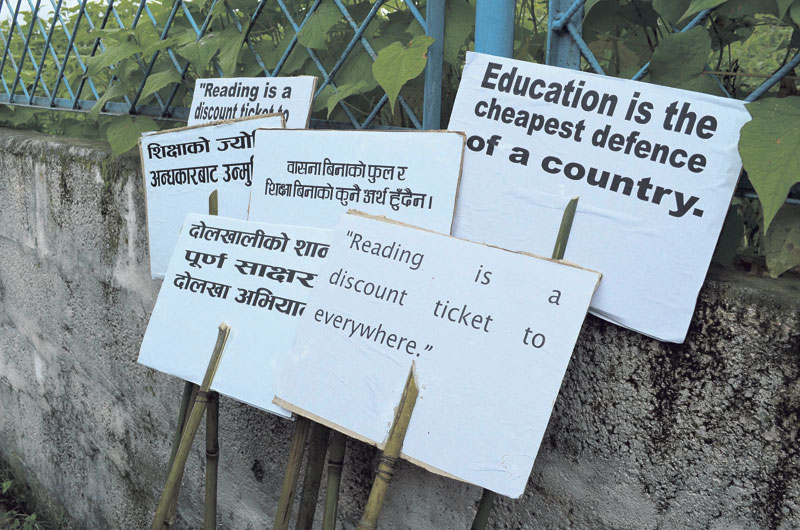

Hundreds of people took part in the rallies that started from Tundikhel area and marched through the Charikot bazaar before ending in an indoor event, which eventually declared Dolakha a ‘literate’ district. The event—held inside a local party palace—consisted of political speeches, including one by the Minister for Education, Giriraj Mani Pokharel, dance numbers, and drama performances.

Nepal’s current literacy campaign is a part of an ambitious global goal of Education for All. The newly promulgated constitution of Nepal has also guaranteed the right of every citizen to basic education. Started in 2009, the National Literacy Campaign (NLC) had a “target to eradicate illiteracy from the country within two years time frame.”

Now in its seventh year, the NLC is lagging behind in achieving the goal of putting illiteracy to an end, and faces fresh challenges following the earthquakes of 2015. Among many, one big challenge has been the failure to continuously run the non-formal literacy classes in post-earthquake situation as people’s basic needs of shelter, food, water and health have emerged as renewed priorities.

Yam Bahadur Gurung of remote Orang Village Development Committee (VDC) of Dolakha district has not witnessed any non-formal education program running in his village after the ravaging earthquakes of last year. Deepak Thakuri of the same VDC also states that there have not been any classes held since the earthquakes. He believes that there are still many people who cannot write their names in his VDC.

Thakuri thus questions the intention of declaring the district as a literate one. However, he believes that some people have made dramatic progress through non-formal education classes. A Tamang woman from his VDC, he says, is now able to thoroughly read the textbooks of grade seven and eight.

However, keeping people motivated to take part in literacy classes is another challenge in rural areas. Thakuri states that even when the classes were running, some people aren’t all that enthusiastic and motivated to attend classes because for them agriculture and household chores were more important than being able to write their names.

Speaking at the program, Minister Pokharel pointed out the challenges in the current education system, one of which is the existing gap between private and public educational institutions. Reports demonstrate that there are huge gaps in literacy rates between men and women and between urban and rural areas. For example, Non-Formal Education Center’s Status Report 2014-2015 shows that adult literacy rates (15+ years of age) among men and women in urban area are 90.5 and 74, whereas in rural areas the rates are 71.6 and 47.1 respectively. Similarly, the total adult literacy rate in urban areas, according to 2012/13 Annual Household Survey, is 81.6, way higher than that in rural areas which is only 57.8.

Another serious challenge to adult literacy campaign is the likelihood of reversal to illiteracy even after someone is literate, particularly because of lack of continuing literacy classes and practices in everyday life. When people cannot engage themselves in literacy-related activities for some time, they may forget the late acquired knowledge and skills. This, then, raises an important question regarding government’s (lack of) vision for post-literacy program. Without clear plans and strategies for such a program, it is likely that the declarations might just be limited to records.

Rijal is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at Simon Fraser University, Canada

br.kavyi@gmail.com

You May Like This

Smoke-free indoor campaigns gather dust

ROLPA, Sept 4: The smoke-free indoors campaign has remained in limbo in Rolpa district. ... Read More...

Alliances found breaching election laws during poll campaigns

RASUWA, Nov 5: Cadres and leaders of both the left and right forces in Rasuwa have been found organizing their poll... Read More...

Candidates spending millions for campaigns

MYAGDI, May 11: Breaching the election code of conduct, candidates for the post of ward chief in Myagdi district are spending... Read More...

Just In

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

- Speaker Ghimire administers oath of office and Secrecy to JSP lawmaker Khan

_20240419161455.jpg)

Leave A Comment