OR

Little had changed in the lives of people, even though appearances of changes like advent of Maoism and demise of monarchy were aplenty

This story is worth telling because of the worthiness of the events that engulfed the nation 27 years ago on April 9, 1990, which very few people now seem to remember or to care about even if they do remember.

It was late in the afternoon of April 9 in 1990 here in Washington DC when news flashed out from Kathmandu that King Birendra had agreed to restore multiparty democracy. The fight between democratic forces and king’s supporters had been intensifying over the past few months, culminating in the shooting to death a few days earlier of dozens of protesters by military forces in the heart of Kathmandu.

Skirmishes between protestors and the police had occurred on several occasions, in many parts of the country, ever since the overthrow of the democratically elected government of BP Koirala in December 1960. However, the deaths of such a large number of unarmed protestors, as happened in 1990, were unprecedented.

The military had pushed for use of force to subdue protestors but King Birendra was wise enough to foresee the unfolding scenario far into the future, which convinced him that he couldn’t survive without making a compromise with the opposition. Without further ado, the king invited four leaders of the opposition to his palace near midnight of April 9—just three days after the most egregious killings of protestors near Annapurna Hotel right in front of the royal palace—and told them that he agreed to their demand for restoration of multiparty democracy and that this was to take effect immediately.

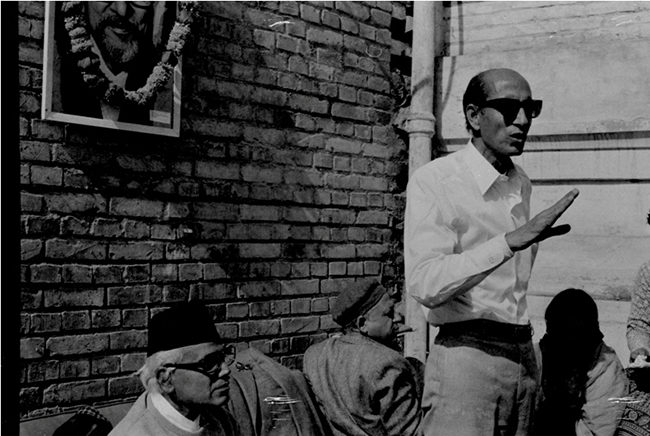

Girija Prasad Koirala addressing a mass while Krishna Prasad Bhattarai sits on the dais. (Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya)

Unfortunately, despite the massive sacrifices made by the people for the restoration of democracy, virtually no memorial of this struggle exists today. This, in effect, shows how little things had changed in the daily lives of people, even though outward appearances of changes were aplenty, most prominently seen with the advent of Maoism and the demise of monarchy. Such erosion in significance of a significant period in our history says much about the character of democracy that we inherited and democratic governance that ensued after the 1990 change.

The nonperformance of democracy, as has been observed until now, is rooted in the way heirs to democracy approached the political transition of 1990. This fracture in democratic governance emerged almost overnight after the king yielded power and picked the senior-most Nepali Congress leader, Ganeshman Singh, to lead the next government.

Singh, however, declined the offer, instead recommending KP Bhattarai as new prime minister, to which the king agreed. Bhattarai accepted the job. With his reputation as a founding member of Congress party, his well-known commitment to democracy, and his close collaboration with the legendary BP Koirala, Bhattarai had the credential to head the new democratic government.

Unfortunately, Bhattarai’s reign was rocky from the start, first due to his lack of leadership qualities and then his lack of commitment to make any substantive changes that were improvements to the earlier Panchayat rule. At the same time, Bhattarai’s leadership was undermined by noncooperation from another Congress leader, GP Koirala, who also claimed eminence for being the younger brother of BP Koirala.

Bhattarai did nothing to cement the democratic rule and very much acted like he was happy to continue to take orders from the king. He chose to leave all the Panchayat structures in place except suspending the zonal commissioners and scuttling zonal divisions of the country. He persecuted no one, jailed no one, and confiscated no one’s property, which was called for in the face of rampant abuse of power by high officials of the Panchayat regime. A stark example of Bhattarai’s non-performance and non-assertion of democracy was that he left the Panchayat appointee for ambassador to Washington in place for eight months after the change.

Perhaps Bhattarai’s lack of ambition and unwillingness to act like a leader encouraged GP Koirala to challenge his leadership. GPK was a shrewd politician against whom Bhattarai was no match. He out-maneuvered Bhattarai and downsized his authority as the party leader. GPK was quick to claim the prime minister’s chair right after Bhattarai’s term as Interim Prime Minister expired.

Koirala prepared a battalion-size force of committed cadres to undermine Bhattarai’s chances in the 1991 parliamentary election, as a defeat would have automatically disqualified Bhattarai from becoming prime minister, and thereby guaranteeing Koirala’s own elevation to the post. Actual events unfolded pretty much according to his plan, as Bhattarai was defeated while Koirala won and became the prime minister.

The resolve that Koirala had showed to undo Bhattarai and assume government leadership should have proved something of a boon to Congress. The occasion could have been used to allow democracy to take root under strong leadership of Koirala, which also would have served his own ambition to be the new strongman. Unfortunately, Koirala devoted much of his leadership in a sort of a clean-up operation of his party and bureaucracy, ousting anyone whose loyalty he doubted and, especially, those close to Bhattarai.

A case in point was the dismissal of one close Bhattarai ally and senior Congress leader, Yog Prasad Upadhaya, from his ambassadorship in Washington. As the story goes, Upadhaya had stayed back in Washington to greet Bhattarai, who was scheduled to come to Washington after his medical stop in Canada. Bhattarai’s visit coincided with PM Koirala’s own arrival in New York and Upadhaya was unable to turn up. Koirala took this as evidence of disloyalty and ousted Upadhaya from his job the very next day.

Coming down heavily on Bhattarai wasn’t enough for Koirala and so he took on the revered Congress leader Ganeshman Singh, and forced his exile from the party. Because of Ganeshman’s small constituency that was limited to Kathmandu valley, he couldn’t match Koirala’s nationwide reach. Ganeshman had to leave the party in disgust and spend rest of his life in isolation, unloved and unappreciated for his lifetime of service to the country and, above all, for his key role in ushering a largely bloodless transition to democracy.

The story of April 9, 1990, then, for most parts, begins and ends with GP Koirala, and his role in doing everything to weaken democracy. In 1994 he prematurely resigned as prime minister thereby helping communism take hold in Nepal. Koirala’s mishandling of the transition also encouraged the Maoists to make inroads and, somehow, paved the way for the 2001 royal massacre, followed by the abolition of monarchy in 2006. The republicanism that followed was the final blow to democracy and has helped push Nepal into the ranks of failing states.

The author teaches economics at Northern Virginia Community College in the US

sshah1983@hotmail.com

You May Like This

Early humans survived climate change by becoming more creative and sophisticated

Archaeologists have uncovered new evidence that indicate that early humans were behaving more sophisticatedly, even involved in trading around 100,000... Read More...

Province 3 CM calls for change in work style change for positive results

HETAUDA, Feb 19: Chief Minister of Province 3, Dormani Poudel, has said the change in attitude and work style was... Read More...

‘Things could become more difficult for immigrants in US, but not likely for Nepalis’

Dr Dee (Dianne) Aker who has been a part of the peace building process in Nepal for the past 15... Read More...

Just In

- Gold smuggling case: INTERPOL issues diffusion notice against accused fugitive Jiban Chalaune

- Raya appointed as Auditor General

- 9 are facing charges in what police in Canada say is the biggest gold theft in the country’s history

- Gold price falls by Rs 600 per tola

- Dr Anjan Shakya nominated as National Assembly member

- Special session of Koshi Province Assembly begins

- Lumbini Province: Three UML, one NUP leaders to take oath as ministers without portfolio today

- Unified Socialist’s general convention from June 30

Leave A Comment