OR

Nepal and peacekeeping

More from Author

There is no bureaucratic and political will to promote UN peacekeeping in Nepal

Unlike during the Cold War, today the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations (UNPKO) are multidimensional, with peacekeepers having dynamic responsibilities ranging from maintenance of peace and security to providing humanitarian assistance, human rights protection, protection of civilians, to administrative functions to carrying out development works in conflict areas. Along with the growing complexity of operations, mission partners have also grown diverse.

There is a similarly ‘hybrid mission’ in Darfur (UNAMID), where peacekeepers have to work alongside regional organizations like the African Union, and in the ‘offensive mandated mission’ (MONUSCO) in Congo, where the Intervention Brigade has the mandate to go on the offensive against hostile elements. In such a context, maintaining competency of their troops is a critical challenge for every Troop Contributing Country (TCC).

Nepal has been a reliable UN peacekeeping partner for a long time. For this the credit must go to the Nepal Army. Our legacy goes back to 1958 when five Nepali military observers were deployed in United Nations Observer Group in Lebanon (UNOGIL). Since then Nepal’s contribution to peacekeeping has never receded, resulting in around 115,000 troops serving in 42 missions around the globe.

Currently, from the deserts of Iraq to the forests of Congo, from snow-capped mountains of Golan Heights to insurgency-ridden Somalia and Mali, there are altogether 4,465 Nepali Army peacekeepers serving in 16 different missions, including 121 female soldiers. Similarly, Nepal Police (NP) and Armed Police Force (APF) also have credible presence abroad. As a result, Nepal is the sixth largest TCC in the world.

Indeed, along with institutional and individual benefits, the troop contribution is also serving our national interest and foreign policy, which is guided by the principle of ‘abiding faith in United Nations’ and ‘non-alignment’. Nepal has thus succeeded in building a convincing image in United Nations Organizations.

But despite these successes, Nepal’s days ahead in UN peacekeeping won’t be easy. In a changing geopolitical scenario, more potential contributors are emerging. They are not only forging new space for themselves in peacekeeping but also endangering the contribution of countries like Nepal whose political class is not interested in the venture.

In 2000 Nepal was the fourth largest troop contributor to UN peacekeeping, after Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. But now we come sixth, with Ethiopia and Rwanda having surpassed us. Similarly, China, Indonesia, Ghana, Senegal, Brazil and Malaysia are entering the field with great determination.

‘Professionally our soldiers are more competent compared to other forces in the world, but when it comes to logistics, especially technology and equipment, we lag behind,’ says a Nepali defense analyst. The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) is an example of Nepali peacekeepers competing against their European counterparts like Spanish, Italian and French, who are much more logistically sophisticated and high-tech.

‘As we don’t have substantial presence at decision-making levels, UN Headquarters and field missions for example, our voices remain weak,’ is another lament of participating Nepali peacekeepers. At present only one Nepal Army officer at UN Headquarters in New York takes care of all the peacekeeping issues related to NA, NP and APF.

The situation is not much better inside Nepal. There is next to no bureaucratic and political will to promote Nepal’s peacekeeping efforts, without which the objectives of modern peacekeeping are not attainable.

First and foremost, UN peacekeeping has to be subsumed within our national interests. Without such political priority, there can be no meaningful change. We have a lot to learn from Bangladesh, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Bangladesh started participating in UN peacekeeping in 1988 and is now the third largest TCC. This has happened largely because UN peacekeeping is among her core political interests. Similarly, Malaysia has ‘UN peacekeeping participation’ as an important ingredient of its foreign policy and Indonesia has constitutionally recognized the venture as a national obligation.

Second, there should be an integrated national mechanism where the related officials of ministries of Foreign Affairs, Defense, Home Affairs, Finance, as well as National Planning Commission, are under a single roof and working together. That will ensure optimal use of time and resources.

Third, to produce dynamic peacekeepers, the Birendra Peace Operations Training Center (BPOTC) should be developed into ‘national training institute for peacekeepers’ where troops of all three organizations (NA, NP and APF) can be trained together. After all, in modern peacekeeping, the jobs of ‘polices’ and ‘militaries’ are similar; and the trainings can always be adjusted as per the unique requirements of each of these agencies. Or the BPOTC can be developed into a ‘Regional Academic Institute for UN Peacekeeping’, like Ghana’s ‘Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC)’ where post-graduate students, civil servants, diplomats and security personals pursue their academic studies.

Lastly, ‘peacekeeping is not a soldier’s job but only a soldier can do it’ and Nepali soldiers are undoubtedly among the most reliable peacekeepers. Hence her participation is welcomed not only by the United Nations but also by host nations mired in conflict. But we need to be well prepared. If we don’t adapt to the changing peacekeeping landscape soon, our contribution to UN peacekeeping might keep falling.

The author is currently serving in United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL)

You May Like This

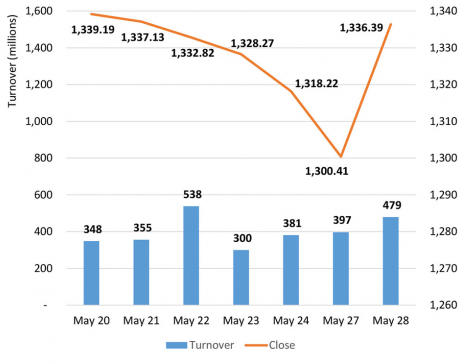

Nepse snaps six-day losing streak

KATHMANDU, May 29: Nepal Stock Exchange (Nepse) index surged 2.77 percent to close at 1,336.39 points on Monday. ... Read More...

Nepal goes down 2-1 to Tajikistan on home ground

KATHMANDU, Sept 6: Nepal suffered a 2-1 defeat at the hands of Tajikistan in the AFC Asian Cup 2019 Qualifiers on... Read More...

Italy ends its losing run against Spain with 2-0 win

SAINT-DENIS, France, June 27: Spain's era of dominance at the European Championship came to an end Monday when Italy beat the... Read More...

Just In

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

- WB to take financial management lead for proposed Upper Arun Project

- Power supply to be affected in parts of Kathmandu Valley today as NEA expedites repair works

- Godepani welcomes over 31,000 foreign tourists in a year

- Private sector leads hydropower generation over government

- Weather expected to be mainly fair in most parts of the country today

- 120 snow leopards found in Dolpa, survey result reveals

- India funds a school building construction in Darchula

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment