OR

Law on political financing

Many anomalies in our political parties can be explained by lack of transparency and accountability in their sourcing and use of funds

Amid growing concerns against mushrooming growth of political parties in Nepal, the consolidated law on political parties that was recently endorsed by the President is, definitely, a step in the right direction. Its one-single article (52), related to recognition for a ‘national party’—a threshold of at least 3 percent of total votes in proportional representation component of election and at least one seat in direct election—has already egged smaller political parties to merge and unify. However, as the saying goes, the proof of the pudding is in the eating: the significance of this law will have to be judged only after its actual enforcement, all of it not just bits and pieces of it. Will this law also meet the fate of the previous Political Parties Act (2002) or will it really give some order to the chaotic Nepali politics?

The new law seeks to consolidate two earlier pieces of legislation related to the management of political parties (the Political Parties Act 2002 and the Defection Act 1997) and has been designed to implement the constitutional provision on establishment and functioning of political parties. The law covers many aspects like registration and deregistration of political parties, their internal workings, party defection and settlement of party disputes, transparency and disclosure requirements, and sanctions and punishments. In this write up, I will take up the new provisions related to party funding.

As many anomalies in our political parties can be explained by lack of transparency and accountability in sourcing and use of funds, political party financing has become a crucial issue for the sustainability of our democracy. In today’s competitive world, no party can survive without money. For a political party, money acts like blood does for living beings.

But there is dilemma when it comes to money in politics: both too little and too much of it are bad. Moreover, there is also an issue of quality of money being supplied, i.e., politics must be kept free of bad or dirty money.

Earlier, the political parties were required to disclose the names, addresses and occupations of the persons and the corporate bodies contributing more than Rs 25,000; failure to do so would result in the puny fine of Rs100. (This legal provision looked more like a joke than a serious attempt to regulate party financing.)

The new law contains separate chapters on party funding, its use, and accounting and audit requirements. Political parties are allowed to have only voluntary, as against forced, financial contributions from Nepali citizens and corporate bodies. But the new law categorically states conditions for accepting voluntary donations. It has new conditions for accepting donations exceeding Rs 25,000. These include: a) the money must be deposited in the bank through checks or bank transfers, b) there should be receipts for such donations, c) donors must disclose the sources of their money, d) the contributions should not be a quid pro quo or reciprocal transaction, and f) if any of these requirements are breached, both giver and receiver will be liable for punishment.

The new law also specifies negative list of institutions and bodies, from which political parties cannot receive voluntary contributions. These prohibited bodies include: a) agencies of federal, provincial and local governments of Nepal, b) corporate bodies with full or partial ownership or control of federal, provincial or local government, c) public limited companies, d) government or community university, college, school or any academic or educational institution, e) NGOs and INGOs, f) foreign governments, organizations or persons, g) undisclosed persons or organizations, and h) organizations specified by the Election Commission.

The paltry penalty of Rs 100 has been replaced by harsher punishments. In case of a breach, the Election Commission can warn political parties, prevent them from participating in elections or even annul their registration. The commission may also levy fines ranging from Rs 5,000 to Rs 25,000, for various acts of omissions and commissions.

Moreover, the commission may impose a fine, on the person or organization giving voluntary financial assistance in contravention of the provisions in this law, the fine equal to the amount of such assistance.

When it comes to money in politics or political party financing there are two, albeit, related issues. One is campaign financing. This is related to how political parties mobilizing funds for their election campaigns. This issue is guided by electoral codes. For example, the Election Commission has prescribed expenditure limits for local election and also a strict code of conduct. Second, there is also the issue of running party offices.

Much of what is being discussed above is related to this. By and large, on party financing, for both election campaigns and running office, our emphasis has been on regulation and monitoring. But in the absence of strong regulating capacity of the Election Commission, this approach will have limited impact on operation and functioning of political parties.

In the negative list of institutions from which political parties are not allowed to receive donations, it is surprising to see only academic and educational institutions. If service delivery is the key point here, why have hospitals and transport services also not been exempted? Clearly, some vested interests were involved in the drafting of this law. There is now great chance of the institutions exempted from the negative list will be endlessly harassed for ‘voluntary’ contributions. The law is also silent on non-cash donations and contributions.

Interestingly, we continue to be guided by conventional policing methods: if there are no complaints, there are no crimes. The Election Commission will not initiate action unless formal complaints are filed against political parties. Also, if political parties are unduly restricted from raising funds, they will continue to rely on their old and often illegal methods. A single threshold provision related to recognition of a national political party has created a ruckus among small parties. We need a similar approach to party financing. This may even call for possible state funding. Given the high level of political competition and high cost of elections and running party offices, it is about time that we emerged from this old regulatory approach. What we rather need is some kind of a distributive approach so that we can’t minimize the impact of dirty money on politics.

The author is a freelance management consultant

narayan.manandhar@gmail.com

You May Like This

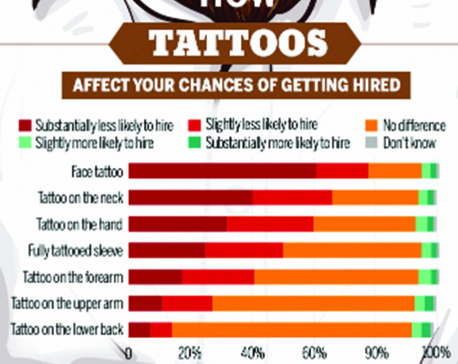

Infographics: Your tattoo could prevent you from getting your dream job

Having a tattoo reduces your chances of getting a job, says a recent report. Face tattoos irk employers the most. Read More...

If you are lucky, you will find the heart to listen to you!

Stress has become the go-to word for everyone in the modern word. It has become the reason for being unnecessarily... Read More...

Can your fingertips unleash the genius in you?

KATHMANDU, March 22: The patterns on your fingers not only define your sole identity but also the attributes and multiple intelligences... Read More...

Just In

- MoHP cautions docs working in govt hospitals not to work in private ones

- Over 400,000 tourists visited Mustang by road last year

- 19 hydropower projects to be showcased at investment summit

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment