OR

It is hard to believe Upendra Yadav once went to ex-Bihar Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav, bowl in hand, exhorting him to support the blockade.

The Federal Socialist Forum Nepal (FSFN) President Upendra Yadav left me in disbelief last week. He was frank and forthcoming. I had reached his Tinkune office half an hour later than the appointed time—of course due to frustrating traffic—but he did not seem to mind. This was unexpected. Even more unexpected was what he said.

Yadav said his decision to partake in all elections was a compromise for “the people and the country,” because “national interest should be at the core of every political movement” and that he was participating in local polls (both phases) so as to be a part of constitution implementation process. “Protecting national interest, promoting feeling of nationalism and national unity” is his key goal, he said. Focus of a political party should be on economic development as much as on political and civil rights. He cited examples from Liberia, Somalia and Kenya to explain how countries that focused only on identity and rights issues without taking care of economic agenda have fallen into “ruins.”

On the economy, he sounded like Ram Sharan Mahat, on ethnic identity issue he was a conciliator rather than a hardliner, and on nation, nationality and nationalism he echoed CPN-UML Chairman KP Oli. In many places I felt he was speaking my mind (see his interview: “RJPN is a stranded ship that has lost its compass,” Republica, June 8).

This was not the Upendra Yadav I and my colleague Biswas Baral had met in September, 2016.

Back then Yadav responded to our queries with reservation and with a tinge of anger. He was dead against compromise of any kind and said “there is a strong voice in Madhes for armed struggle” and that the continued confrontation between Madhes and Kathmandu could “lead the country to an unthinkable disaster.” He was angry that local level units have not been put under provincial jurisdictions. He dismissed local election as a strategy of sasak barga (ruling class) to sabotage federal course. “Unless the constitution is amended, there cannot be any election in Nepal,” he warned. He sounded like he was wishing for the constitution that was “already on a path to failure” to fail absolutely.

Yadav, we concluded, was not keen on constitution implementation.

That was ten months ago.

Upendra Yadav has come a long way since 2006. The 2006 Madhes Movement gave him a savior-like status in Tarai-Madhes. As someone who made to Singha Durbar only once (as a foreign minister in Pushpa Kamal Dahal government in 2009), Yadav, unlike many other Madhesi leaders, does not have baggage of corruption and abuse of power.

But during 2015/16 blockade and Madhes protest, he demonstrated typical characteristics of racism and bigotry. He was one of those who delivered hate speech to incite local Tharus to retaliate against Pahades in Kalali. The National Human Rights Commission concluded in March 2017 that provocative speeches by leaders (one of them Yadav) had triggered Kailai carnage.

That is not the Upendra Yadav we have today. It is hard to believe he once went to ex-Bihar Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav, almost bowl in hand, exhorting him to support border blockade. It’s hard to believe he once advocated and held the country hostage demanding complete separation of plains from hills in federal demarcation.

Predictably, his colleagues in Rastriya Janata Party Nepal and Madhesi intellectuals have derided him as a ‘revisionist’ and ‘compromiser.’ They have accused him of submitting Madhes agenda to the ‘racist state.’ He might have to bear with such vitriol for some time to come.

We don’t know what actually triggered the change of heart in Yadav or how long he will stick to his ‘nation first’ stand. In Nepal, politicians change color like chameleons. We don’t know what led Yadav, who once presented himself as the symbol of divisive politics, to now prioritize hill-plain unity, development and prosperity.

Perhaps because those who are said to be providing funds to his party saw no future in investing in his cause, perhaps Yadav realized he was in the wrong direction, perhaps he thinks he will be able to make an impact in Nepali politics only when he can rise above regional politics, or perhaps he realized the actors and intelligentsia he had relied on in the past were bent on pushing the country to endless chaos—we won’t know unless he comes clean on this himself. Whatever the reason, his U-turn at this point means a lot in national politics and for this he should be thanked.

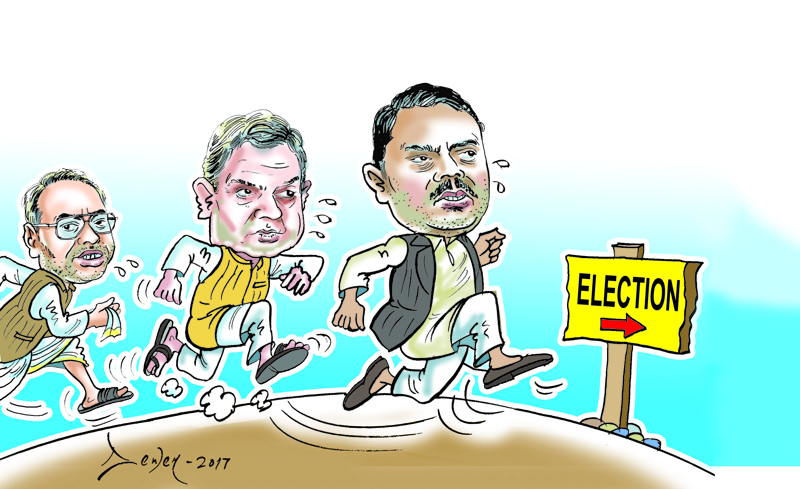

For one, with FSFN on election board, he has left almost no option for RJPN leaders but to join the second phase. If they stay out, they might lose their political space to FSFN, Nepali Congress or even CPN-UML. The restlessness in RJPN rank and file is also apparent. While leaders are threatening obstruction, boycott and protests in Kathmandu, cadres on the ground are secretly campaigning.

RJPN has a difficult choice: come join election and be part of constitution implementation or collude with secessionists to fuel violence so that innocent people get killed, which in turn can be used as an excuse to defer election or can be sold for electoral gains or to justify their possible tilt towards secessionists. Let’s believe RJPN leaders won’t opt for this destabilizing and dangerous option.

RJPN leaders, like Upendra Yadav, will also have to come to a kind of compromise, sooner or later.

Broadly, Yadav’s conciliatory gesture reflects what’s fundamentally wrong with the way politicians in Nepal do politics.

Yadav and his colleagues in RJPN today had started 2015 Madhes Movement on the foundation of hate and propaganda. They promised to hive off entire Madhes from hills to create provinces, and projected hill dwellers, rather than those few at the helm, as ‘enemies’ of Madhes. They interpreted remarks of few hill leaders in Kathmandu as collective voice of hill community towards Madhes. So their demands veered from one extreme to another. They later presented a 26-point demand as their bottom line, and next they came up with 11-point demand.

Today they have made declaration of martyrdom for those killed in police clash, compensation for the victims, and withdrawal of cases against their cadres minimum conditions for ‘creating an environment for them to join the election.’ When you begin with wrong premises, you do not reach the right goal. When you start out with agendas founded on emotions rather than reasons, agendas which broader section of the society thinks are wrong, compromise is where every such movement ends.

Madhesi leaders have rightly said current amendment bill is flexible compared to what they had been demanding in 2015. For the foreseeable future nothing more may be done on citizenship (rather than tweaking provisions here and there) or letting Federal Commission to settle the federal boundaries.

Already they have interpreted it as a sign of the ‘oppressive and affluent’ Khas Arya not conceding to genuine demands of ‘oppressed’ Madhesis. But come to think of it: when certain Madhesi agendas can’t even be met by a government amicable to Madhesi interests , and a compromise solution is opposed across party lines, rather than blaming those critical of those demands as ‘enemies of Madhes,’ it would also be wise to review viability of those demands.

However high you climb the ladder of radicalism and emotionality, in politics, sooner or later you will have to come to real ground. Every radical and aggressive posture is finally tested on platform of rationalism and pragmatism. Anarchism has the power to wreck damage, sometimes irreversible, but it does not last.

Upendra Yadav seems to have taken this message to his heart. RJPN leaders should follow suit. Have faith in your followers and they will vote for you.

Twitter: @mahabirpaudyal

You May Like This

After securing ODI status in Zimbabwe, Nepali cricketers return home

KATHMANDU, March 20: The national cricket team has returned home on Monday from Zimbabwe after securing the One Day International (ODI)... Read More...

Kohli confirms Rahul return, Mukund faces India axe

COLOMBO, August 2: India captain Virat Kohli has confirmed that fit-again opening batsman KL Rahul will return to the side... Read More...

China astronauts return from month-long space station stay

BEIJING, Nov 18: A pair of Chinese astronauts have returned from a month-long stay in the country's space station, China's sixth... Read More...

Just In

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

Leave A Comment