OR

STUDENT ROLE IN SEMESTER SYSTEM

Shyam Sharma

The author teaches writing and rhetoric at the State University of New York in Stony Brook. He can be reached at shyam.sharma@stonybrook.edughanashyam.sharma@stonybrook.edu

Even when we know how we are supposed to behave in a new system, we don’t realize we are resisting or not making the shift.

As they shift from the traditional exam-driven higher education to more student-engaged semester system, teachers who I have worked with have emphasized that it is hard to change student expectations and response. Making this major shift in Nepal’s higher education will involve training and education, resource and leadership, and shifting of professional reward and incentive on the part of the teachers.

I have written about this issue here before and I intend to explore more specific issues in the future. In this piece, I would like to speak directly to (or talk specifically about) students: What roles can students play as their universities shift from annual to semester system? How can they make their own learning and their teachers’ teaching more productive as the latter try to make the transition?

For illustration, let me start with a brief anecdote. Every Thursday evening, week after week, a professor of applied linguistics used to walk into the class, greet students, and ask: “So, what do you guys think about the readings for today?” That puzzled me. I was able to overcome the first challenge of transitioning into a semester-based system: I went to class having read the texts that were listed on the course schedule. But I still did not like that students took up most of the three hours, especially because I didn’t like having to listen to their “opinions” instead of to the actual expert in the room. Expressions like “I think that…,” “In my opinion…” and “Well, to be honest…” were at first rather irritating.

After a few weeks, I was so frustrated that I decided to join the conversation. In particular, I wanted to challenge an older student (with a strange hairstyle) in the front row whose “opinions” were typically based on superficial understanding of the text but who made them sound important! Magic happened—for me, that is. I loved participating, sharing my own understanding and perspectives, critique and analysis, synthesis and application of the ideas we were studying. It was then that I realized that I was refusing to change my old habits and expectations shaped by the traditional teacher/lecture-dominated, exam-driven, and content-focused education system in Nepal.

I expected the teacher to engage us with her level of understanding of diachronic linguistics; the teacher expected her students, especially at that level, to start developing their own ideas and take their own intellectual positions in response to scholars in the field, to develop a sense of professional identity and confidence as scholars. As such, other graduate courses focused on developing our own research projects and agenda, creating and trying teaching strategies (we envisioned becoming college professors), and studying and presenting on a variety of topics including information technology and cross-cultural communication.

When I started participating and was gradually challenged to take responsibility and ownership of my own education and to situate that in the context of my own professional career interests, higher education made a whole lot more sense and it was a whole lot more exciting.

Let me further unpack the broader issues about students making the shift from teacher-driven to student-engaged higher education. These are essentially suggestions for graduate-level students in the context of the major shift happening in Nepali higher education. But they are also issues that academic institutions, instructors and academic leaders alike should consider when developing and implementing policies, programs, and practices as part of the shift they are making from their end with the semester system.

First, students can start by making simpler, “technical” changes on how they study. In the more student-centered systems of education, the process puts a lot more demand, so students should develop skills for managing time, stress and information. There will be more deadlines (than the one final exam), unfamiliar types of assignments, and demands for doing and presenting tasks independently. Students should not hesitate to adopt new habits (such as writing down thoughts and scheduling events), new strategies (setting alarms, using mindfulness), and tools and technologies for working on a timeline, especially trying to complete full drafts and milestones ahead of final deadline. They may also need to acknowledge stress and seek mentoring/counseling, as they may not have before.

Second, as professors shift from the older one-way-traffic flow of knowledge to more student-centered teaching, students must respond to that shift by preparing to be engaged, developing a voice and pursuing education with a purpose. This means meeting with the instructor outside class, bringing specific questions to such meetings, and taking responsibility to make the conversation productive. It also means sharing one’s interest, building a professional relationship, and giving the instructor the opportunity to know and be able to recognize one’s efforts when the occasion arises. This is particularly useful when instructors need to write recommendation letters; they can have many and good things to say.

Third, students must understand the objective of each course, such as that expressed in the course syllabus and in the design and objectives of specific assignments. They should also contextualize that objective with their own educational and professional goals. For instance, a case study assignment in a social science course may be designed to expose students to the community, help them learn to tackle challenges in the process of gathering data, and give them the opportunity and support for interpreting and presenting findings from the research. In other words, students must look beyond just completing the assignment, getting a grade, and moving on—for that moving on is moving on to something.

Fourth, students must understand the broader context of education, including the context of professionalization in the university and their own professional aspirations. It is for students to connect what they read for their management theory course with their interest in becoming managers. They can best do this if they make text-to-self connections by taking intellectual positions based on their personal experiences and developing their own ideas about the subject. They should also make text-to-world connections, such as situating what they’re learning with their social and professional contexts, or at least try and make text-to-text connections. Instead of viewing education as an end unto itself, they should consider what they are going to take to the workforce or further education, how they’re going to apply theory, make decisions, and so on.

Finally, because the change in the design of higher education changes role-relations, students should honor their role and that of their professors, their peers, their institution, and others. For example, where professors shift from preparing students to take final/external exams to judging students’ work/performance for 40 percent of course credit, students can disrupt the system by politicizing, trying to corrupt, or otherwise undermining the professionalism and trust on which the success of such a system depends. Nepali student organizations, which are politicized and often even poisonous to professionalism, must shift their role to enhancing the learning environment, adding resources, and creating a new kind of academic culture for the new century.

Neither the educational shift nor the abovementioned suggestions are unique to a particular culture. They are no more common in Europe than in Japan. It is just that certain approaches to teaching and learning have been made more prominent by social, political, economic and technological changes. As I discussed in an earlier essay here, the greatest driver of changes in higher education is the increasing domination of knowledge economy in societies that used to be (or still are) primarily subsistence-based, agricultural, or service-focused.

Also, the shift in education and the changing roles that students (as well as teachers and institutions) must play are in the interest of students. It is just that we find change hard, so much so that even when we know how we are supposed to behave when we move into a new system, we don’t realize we are resisting or not making the shift.

The experience I shared above may have been a bit dramatic—because it was not just classroom practices that changed but the entire university setting, broader social and cultural contexts, and the ways in which everyone around me said and did things in the classroom—but shift in educational practice can itself be overwhelming to students. So I hope some of the advice in this essay will help student readers tackle new challenges and provide others some food for thought.

The author is an assistant professor of

Writing and Rhetoric at Stony Brook

University (State University of New York)

ghanashyam.sharma@stonybrook.edu

You May Like This

Lessons to learn

Better late than never, the government withdrew the controversial Guthi Bill on Tuesday. That was the only way out since... Read More...

10,000 people to learn Marxism

KATHMANDU, September 3: Karl Marx Centenary Organization Committee has decided to educate Marxism to 10,000 people. ... Read More...

Learn to say ‘no’

It’s only by saying no that you can concentrate on the things that are really important. ... Read More...

Just In

- Rainbow tourism int'l conference kicks off

- Over 200,000 devotees throng Maha Kumbha Mela at Barahakshetra

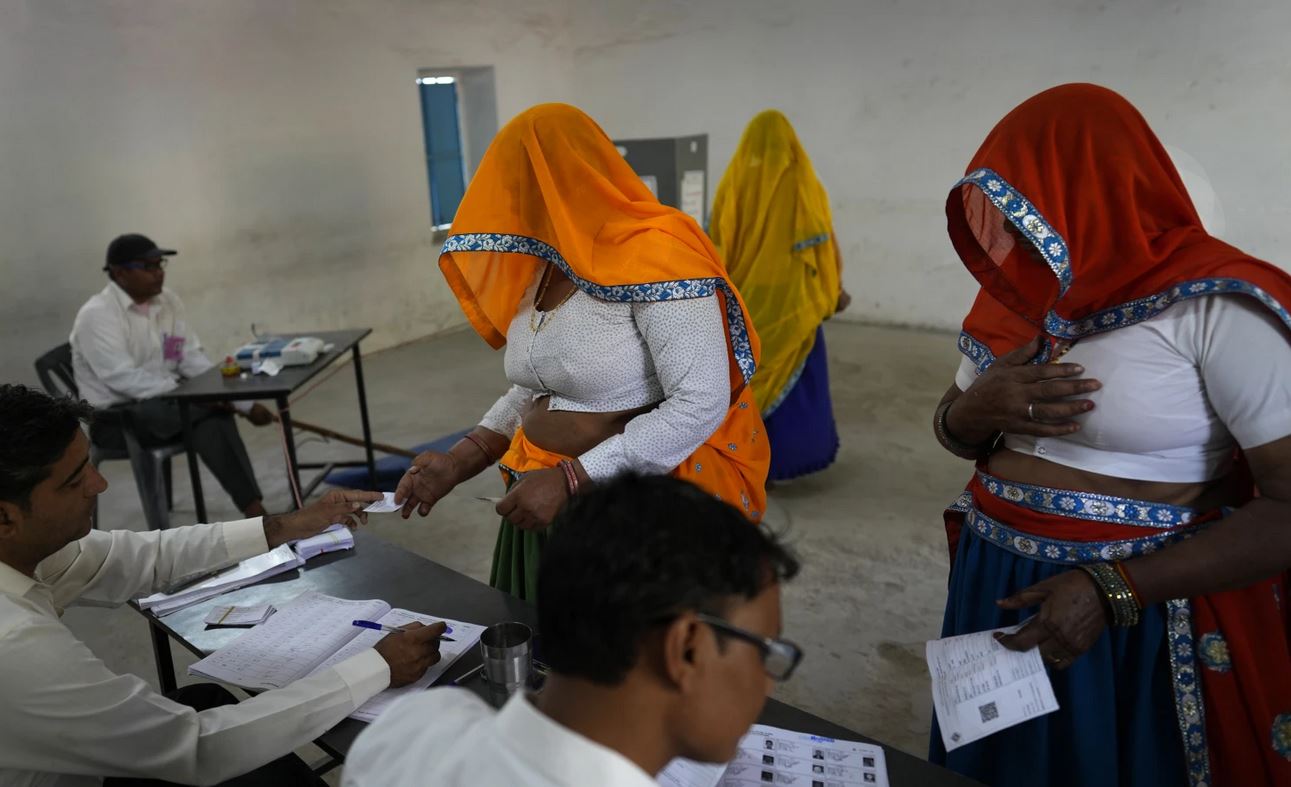

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment