OR

There is no “number two” in Russia. There is only Putin, controlling the FSB, the courts, and the commanding heights of the economy.

MOSCOW: President Vladimir Putin’s regime is as sphinxlike as any that has ever ruled Russia, and now there is a new mystery afoot. Is Igor Sechin—perhaps the most powerful of the St. Petersburg siloviki who helped establish Putin’s regime 18 years ago—about to fall?

The siloviki, the grey men who emerged from the security and military apparatus, have ruled the roost in Russia for the last generation. Sechin had a more substantial KGB career than Putin himself and has held many of the key posts in his patron’s administration. Since 2012, he has been CEO of the state-owned oil giant Rosneft, Russia’s third-largest company (after Gazprom and Lukoil), whose board chairman since September is former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder.

Under Sechin’s leadership, Rosneft has become a state within a state, with quarter-million employees, US $65 billion in revenue, and 50 subsidiaries at home and abroad—as many as Gazprom. And Rosneft, even more than Gazprom, has pioneered the modus operandi of the Putin system since 2004, when it took over the assets of Yukos, following the imprisonment of the company’s head, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a Putin opponent, on fraud and embezzlement charges.

Sechin has always had a direct line to Putin. Many Russians have long assumed that he is also the eyes and ears of the KGB’s successor, the Federal Security Service (FSB), in the natural-resource sector, which forms the core of Russia’s economy and is the hub of the country’s corrupt power networks.

Appearance can deceive

Yet, today, Sechin is involved in a very public—and symbolically significant—courtroom fight. He has been summoned three times by a Moscow criminal court to testify in a case against Alexei Ulyukaev, a former minister of economic development. But Sechin has consistently failed to appear, with his office recently told the court that he wouldn’t be available until next year.

Sechin’s excuses for not showing up have been pretty standard: the summons was lost, and his schedule—which included big government trips to Vietnam and Turkey—did not allow it. But there is nothing standard about a Russian court ordering a figure of Sechin’s stature to testify publicly. On the contrary, in the world of Kremlin politics, the move is as bizarre as it gets.

It all began a year ago, when Ulyukaev was detained at Rosneft’s Moscow headquarters, where he was allegedly attempting to secure a $2 million bribe from Sechin, in exchange for his support for Rosneft’s planned acquisition of a majority of state shares in Bashneft, a regional oil company. Sechin had, after a previous conversation on the topic, reported Ulyukaev to the FSB, who was waiting to take the minister into custody.

Yet bribery is how Russia operates, so the decision to pursue a bribery case against a powerful player is never just about the rule of law. In this case, the real motivation behind Sechin’s decision to go after Ulyukaev is uncertain. Perhaps he felt that the minister needed reminding of his place in the rigid Kremlin hierarchy. Or perhaps, as has been rumored, Ulyukaev was working with other officials to rein in Sechin by stopping Rosneft from acquiring the Bashneft shares.

In any case, Sechin’s plan—about which Putin may well have known nothing—soon backfired, as the legal proceedings became public. Particularly damning, transcripts of Sechin’s secret recordings of his conversation with Ulyukaev—part of a sting operation in which Sechin played a leading role—were disclosed in September.

Putin bares teeth

Sechin called the court’s decision to open the case to the public “professional cretinism.” He claims that “cases like this should be closed from all sides,” because “they contain state secrets.” But the truth is that Sechin was both arrogant and a fool to assume that he would not get dragged into the case.

Of course, given Sechin’s role in entrapping Ulyukaev, logic dictates that he should have been the first witness called. But, in Russia, powerful or famous figures—such as, for example, Khodorkovsky—do not become embroiled in legal cases without the Kremlin’s explicit approval. No low-level Moscow court judge or prosecutor could possibly have summoned Sechin unilaterally.

So when Sechin was called as the last witness—unlucky number 13—there was only one logical conclusion: Putin, who has already ousted a number of the leading siloviki who brought him to power, had decided to take Sechin down a peg or two. The gray cardinal of Rosneft had stepped too far out of line.

As in the Khodorkovsky case, the Kremlin seems to be using the courtroom as a platform for clarifying the positions of the Russian elite. This is particularly important in the run-up to the 2018 presidential election, not least because it is rumored that Putin is seeking a trusted flunky to take over his post, at least temporarily.

Even if Putin does run again—the more likely outcome, given his penchant for total control—he will be seeking a subservient prime minister. The current one, Dmitri Medvedev, has been discredited as inefficient and—to a public that views him as a political pygmy—unworthy of the level of personal corruption that has been exposed.

By going after one of Putin’s ministers, Sechin appeared to be flexing his muscles, perhaps believing that this would prove his readiness as a prime-time political player. Instead, the episode has merely shown, yet again, that there is no real “number two” in Russia; there is only Putin, controlling the FSB, the courts, and the commanding heights of the economy.

Whether Putin decides to remain president or temporarily to fill the post with a puppet, as he did in 2008 with Medvedev, his message could not be clearer: I, and only I am in charge.

The author is Professor of International Affairs and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at The New School

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2017

www.project-syndicate.org

You May Like This

Parliamentary panels acting as govt's mere shadow

KATHMANDU, Sep 24: Instead of working as watchdogs over the government, the parliamentary committees have become loyal to it and favor... Read More...

Nepal Bhasa Movies Under Shadow

KATHMANDU, Sept 10: Awards motivate most of the artists in the world as they are the reorganization of one’s hard work... Read More...

In dragon’s shadow

As India is opposed to China’s BRI and has its own connectivity modality, it could never agree to Nepal’s trilateral... Read More...

Just In

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

- Speaker Ghimire administers oath of office and Secrecy to JSP lawmaker Khan

- In Pictures: Families of Nepalis in Russian Army begin hunger strike

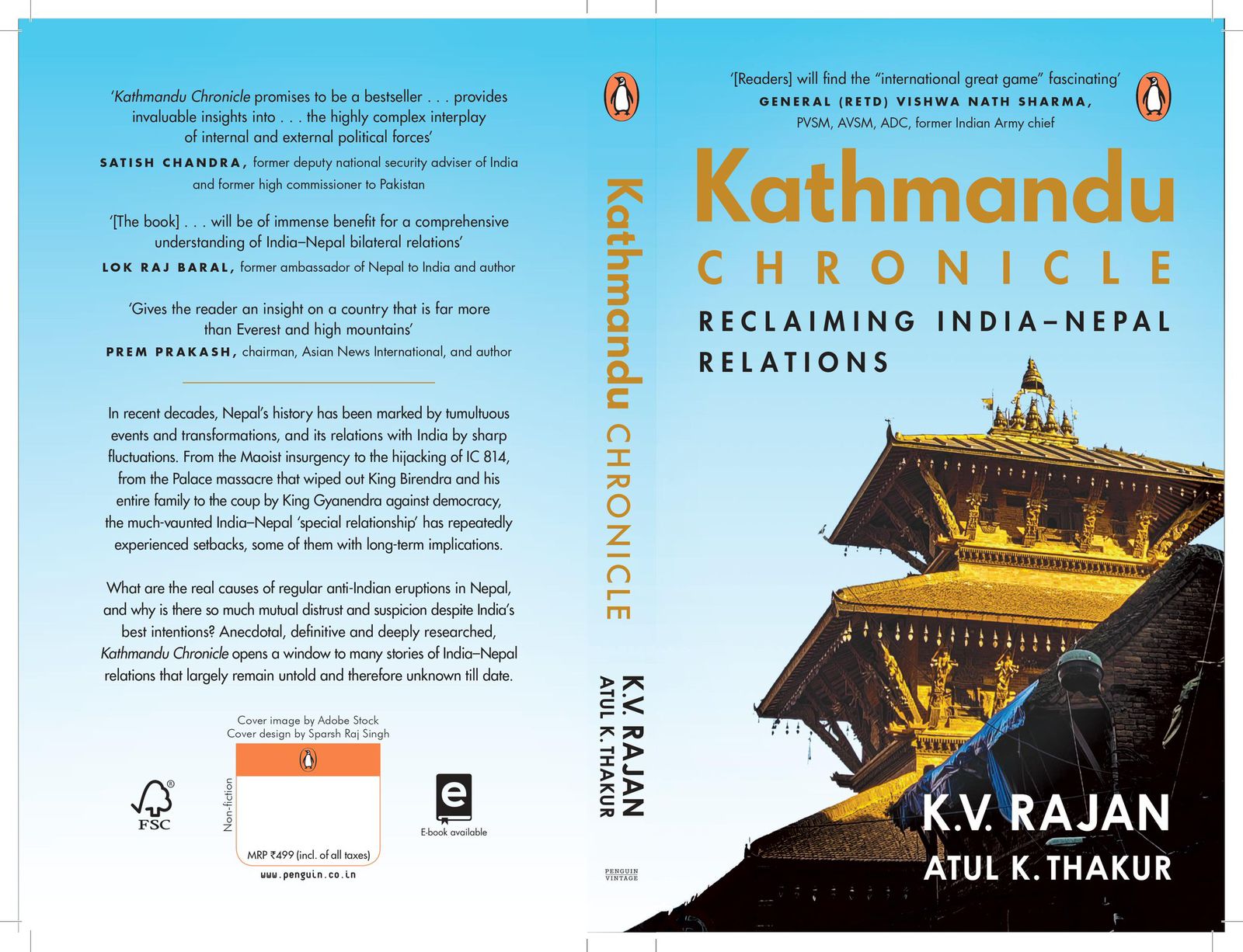

- New book by Ambassador K V Rajan and Atul K Thakur explores complexities of India-Nepal relations

_20240419161455.jpg)

Leave A Comment