OR

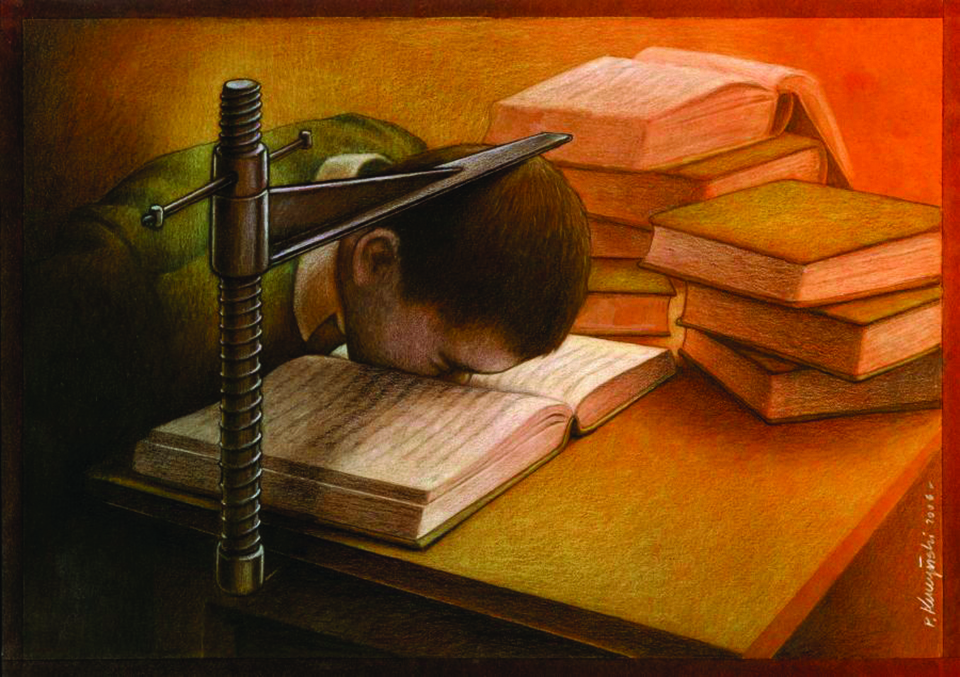

Educators who want to change the system must start by valuing what they already do

After a long, hot day of interviews and class visits in New Delhi two years ago, a colleague and I sat down with a group of students at a tea stall near Hansraj College. I had been wondering why our interview questions with English and communication teachers at the institution had not been eliciting the kinds of answers I was expecting. Our visit was part of a research on how academic writing is described and practiced beyond North America, and a four-member team was gathering data from Colombia, India (my part), Nepal, and Romania.

I was asking a small group of truly enthusiastic young students “how” they learned academic writing if—as I was hearing from them and, earlier, their teachers—the curriculum did not include teaching it exclusively or systematically. The other question was how their education helped them to “engage the world.” What the students said, completing each other’s sentences, threw me off the mode of thinking I realized I had been embracing until then.

“Our teachers teach us about communication but we are practically applying it,” said one student, with another adding, “We use it to communicate with family members around the world through social media.” A third student chimed in: “Plus, college is a wide place [where] we are communicating with a large number of people.” Their collective argument was that students learn to write by putting theory into practice and through experience/exposure.

Working in an educational culture where academic writing is taught in courses involving different skill levels and purposes and specializations, I had clearly come to assume that that educational approach was necessarily the most effective. The students threw a much-needed monkey wrench in the system: they prompted me to think about factors such as student motivation, incidental teaching/learning, and learning while translating knowledge into skills. Students learn to write by imitating, using intuition when faced with needs/challenges, while getting other things done (such as the odd act of creating notes for cheating in the exam).

For me, that moment changed the trajectory of the larger research, helping me understand different contexts and cultures of (writing) education in and on their own terms. That incident helped me see where differently sophisticated conversations about communication, language, and writing were coming from, among students and teachers in different contexts.

Narrative v reality

Unfortunately, dominant discourses about education—such as in my example above regarding teaching and learning academic writing—are framed within narratives, perspectives, and assumptions that don’t match or change with reality. They often lag behind reality. They impede change. For instance, an Indian scholar who contributed a chapter to a US-based book on “writing programs worldwide” described all the things that didn’t exist at his university. His institution was “yet to do” most of the things that are considered academic programs and pedagogies in America. It said little about the same in India.

Our fellow teachers in New Delhi had similarly overlooked how they practically supported students to learn academic writing skills, even as they kept saying that they didn’t have the time to teach it. They taught “writing skills” through theory, practice sessions, language drills, tutorials, exam preps, and so on. They did so with a keen awareness of complex issues that they shared with us, such as power and privilege, language politics, curricular and disciplinary forces, history and economics around writing and language skills. But many of them insisted that they didn’t teach writing.

Observers and researchers from the outside further aggravate the narratives by framing their study on their own terms rather than study local practices in local terms and local contexts.

It is less surprising when people fail to see nuanced and complex pictures of things when they visit new places. It is more problematic than those who look at their own local context—especially because they do so by using the perspectives of somewhere else—create and continue simplistic narratives.

Change is possible

I was reminded of the above challenges when, earlier this month, I was virtually presenting a brief paper at a conference in Kathmandu. I wanted to illustrate by sharing a course syllabus and how, as a teacher, I make micro-level curricular and policy decisions in the classroom beyond ways in which the “system” seems to allow me. I hoped to get the participants to share practical ways in which they did the same.

Midway through the 20-minute discussion, a gentleman at the end of the table started arguing that teachers like him can change nothing about what to teach and how because the system determines everything for them. To my surprise, everyone in the room agreed. They apparently ignored all the things that they can change, modify, replace, or hack—essentially defining curriculum as whatever is given and overlooking the many and small but often consequential decisions that teachers make in the implementation of any curriculum.

I wondered: what makes us focus so exclusively on whatever we cannot change? Why do we keep framing complex issues within common narratives and perspectives and assumptions that only focus on some aspects of the issues? What prompts responses of powerlessness and makes them rather permanent in the minds of a community? What fosters agency, resistance, change?

“There is no time to finish the course,” said one teacher. “We, helmet teachers, as you know, are running from one college to another, so there is no time outside class,” said another. The list was starting to get long when I wanted to pause it and give a pep talk, encouraging teachers to “look at it differently,” see what they already do differently and find and appreciate opportunities to exert their agency.

I was intrigued by how the teachers were describing one aspect of the reality. They skipped parts of it that didn’t fit a single, simple narrative. “We don’t have enough time,” they said, reminding me that a “semester” in Nepal involves a hundred plus hours of teaching time, where I only have forty-five! “We don’t have the power to change anything,” they said, when I could see a wave of change even from the tiny windows of social media and phone conversations. The conference I was joining by Skype was itself a part of a robust new culture of academic conversations I see in Kathmandu. From training and retreat events to journals and research centers, and from educational exchange programs to rich conversations about higher education on social media, there are many signs of positive change in higher education. Somehow, that didn’t seem to matter.

One reason that we stick to a narrative or framing even after the reality has changed or we have stopped doing something is that it is quick and easy to pick up the narrative as points of discussion. I call this “talking point response” that researchers must learn to tackle. Especially when social science scholars ask questions on issues that their interviewees don’t think about on a daily basis, the respondents tend to grab the most common talking points. So, if I ask a dentist to describe what skills her writing involves, she may say, “It’s just technical. I write the same things over and over.” Only when the researcher gains deeper knowledge about the context and issues involved will the dentist engage in deeper, more critical conversation about the nature and function of writing as a communicative tool in the profession.

Especially teachers in academic cultures that depend on hierarchies of expertise, age, or power seem to develop narratives that obscure the richness of local practice, of change, and how individuals’ willpower can collectively make a difference. Their narratives are further reinforced because they also turn their gaze to how “others,” in distant lands and “advanced” societies do things better. And the narratives are reinforced by tourist researchers who believe what they hear and don’t know much about the context to see beyond the dominant narratives—unless they are particularly cautious. Often the vicious cycle continues for generations.

As such, discourses and beliefs about even the most well-studied issue or practice can become ossified because people tend to pick up only what fits established narratives and overlook what doesn’t. When gathering data from informants whose lifeworlds we don’t know much about, researchers need to exercise caution, use self-reflection, and even expect to be lucky!

Even more importantly, educators who want to change the system must start by valuing what they already do. Locally.

You May Like This

Student unions seek educational reforms

KATHMANDU, Feb 7: Various students' unions have demanded that problems existing in the education sector be addressed. ... Read More...

Say no to vandalism in educational sector: N-PABSON

KATHMANDU, July 24: The National Private and Boarding Schools' Association Nepal (N-PABSON) has urged one and all not to cause... Read More...

Develop Central Zoo as an educational hub

KATHMANDU, July 12: With the ever - passionate participation of students in the activities of the Central Zoo, the need... Read More...

Just In

- Rautahat traders call for extended night market hours amid summer heat

- Resignation of JSP minister rejected in Lumbini province

- Russia warns NATO nuclear facilities in Poland could become military target

- 16th Five Year Plan: Govt unveils 40 goals for prosperity (with full list)

- SC hearing on fake Bhutanese refugees case involving ex-deputy PM Rayamajhi today

- Clash erupts between police and agitating locals in Dhanusha, nine tear gas shells fired

- Abducted Mishra rescued after eight hours, six arrested

- Forest fire destroys 13 houses in Khotang

Leave A Comment