OR

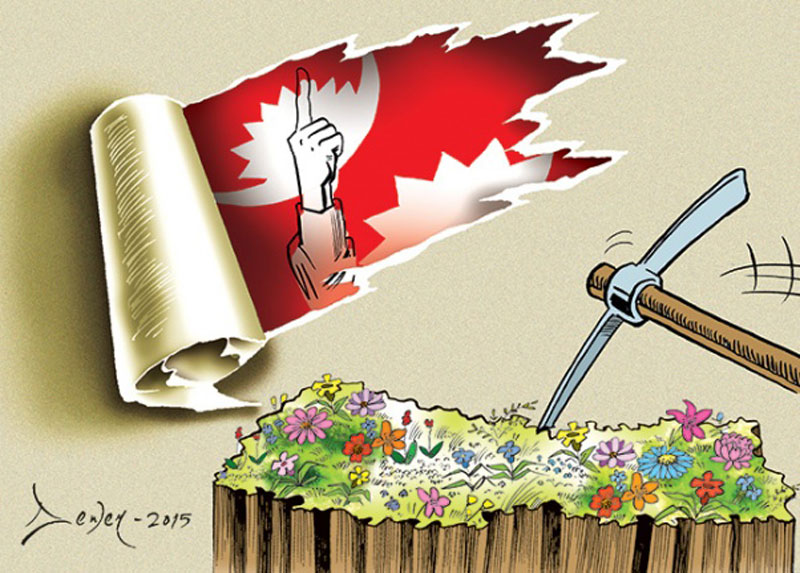

Hill folks have suffered despite their unconditional sacrifice for the country since the start of modern Nepali history

One comment over my previous article (Save the hills to save Nepal, August 10) was that it left out the vital issues of why the hills have been neglected and what will be its long-term repercussions. That might sound like a false proposition when much of the world has understood hills as symbolizing Nepal’s beauty and bravery and, in recent times, cause of all its ills. Therefore this idea needs to be examined against available data and historical context.

Above 75 percent of our parliamentarians represent hills and mountains. This has been the case in the past 26 years of parliamentary democracy. Since the country came into being in the mid-eighteenth century, hill Brahmins and Chhetris have ruled it. Hill men dominate bureaucracy and vital security bodies like Nepal Army and Nepal Police. Thus Nepal’s hills and mountains should have become an example of development and prosperity, wellbeing and happiness. That, everyone knows, is not the case.

Hills and mountains, apart from mounting threats of landslides and other natural disasters, battle scores of other problems. Facts speak for themselves.

Above 2,000 people die in road accidents in Nepal every year—most of the accidents taking place in rural hilly roads, most victims are also hill people. Statistical evidence shows deadly accidents are more common in hill and mountain roads than elsewhere mostly because hill roads are in utter neglect—they have not been properly built, nor are they upgraded and maintained the right way.

Around 1,500 people leave the country every day to escape poverty. Hill and mountain people account for about half of this population: 49.6 percent according to a 2014 status report of the Ministry of Labor and Employment. Most women leaving for Middle East also come from hill districts. According to the UN Human Development Index 2014, poverty defines much of Nepal’s hills and mountains. Food insecurity and lack of health and education infrastructure are common in all hill and mountainous districts.

Hill residents have suffered despite their unconditional sacrifice for the country since the beginning of modern history. Chhetris, Magars and Gurungs of the hills served as loyal warriors during unification and till the latter phases of national expansion.

After Nepal’s capitulation to British India following 1815 Sugauli Treaty, the hill men became what writer Jhalak Subedi calls moharas (sacrificial lambs) of the British Empire.

During the First World War, 200,000 Nepali soldiers—about 20 percent of hill population of that time—fought on behalf of the British. Over 20,000 of them lost their lives. Those who did return from the battlefields came back disfigured, disabled and wounded. But they were not given any compensation.

Historical evidence shows drastic fall in Nepal’s population between World War I and II. Some of the hill villages were left without people. But what did Nepal achieve?

Perhaps the only consolation is recognition of Nepal by the British rulers as a sovereign country. In 1923 Britain signed a peace and friendship treaty with Nepal, which marks the formal beginning of Nepal’s sovereign status because up to that time Nepal-British India relation was guided by Sugauli Treaty which had not accorded sovereign status to Nepal.

Without the 1923 treaty, Independent India could have made us its protectorate.

Twenty one years after the great human loss, the hill men were pushed to another war which had nothing to do with Nepal. Then prime minster Juddha Shamsher offered able-bodied hill youth to British India to fight for them even though the British had made no demands of Nepal. This may have helped Juddha consolidate his power but the country lost thousands of its youths. Some 250,000 British Gurkhas and Nepali soldiers had fought on behalf of Britain during the Second World War. About 32,000 were killed.

The history of World War I and World War II is the history of great human suffering.

Historian Pratyoush Onta has poignantly described the conscription and suffering of Nepal’s British Gorkhas in Dukha during the World War (Himal, Nov/Dec, 1994). “The approximately 2,000 Gurkha recruits a year that were necessary to keep the 20 Gurkha Rifle battalions at full strength were rounded up by labour contractors in Central and East Nepal… When the British required large number of recruits in the fall of 1914, Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher…ordered his district governors to ensure that the supply of “raw materials” was up,” Onta writes.

The fear of forced recruitment, says Onta, was so great during the Second World War that mothers would hide their young sons from the recruiters. The article presents harrowing accounts of survivors—how they fought against hunger, cold and fatigue, how they had to walk over the dead bodies of their own brothers, how Nepali soldiers were often placed on the frontline, how it devastated their family life and so on. The details are disturbing.

Perhaps the third great human loss from the hills happened during the Maoist insurgency (1996-2006). Almost all of the 17,000 people killed, hundreds who were ‘disappeared’ and thousands who were displaced were hill residents.

So one can safely argue that from mid-eighteenth century to 2006, hill men have been made to shed their blood and sweat either for the sake of others or for the hopes that were never materialized. Despite this sacrifice, little has changed in the hills. This is why hill men are deserting their villages in droves every year and descending to the valleys and the plains or taking flight to alien lands for backbreaking jobs.

The political change of 1990 had offered the right opportunity to reward hills for their sacrifice. It did not happen. But why have Nepal’s hills become subject of neglect even after country embarked on democratic polity?

Chairman of Parliament’s Development Committee and CPN-UML leader Rabindra Adhikari admitted that hills had highest representation in political level even before 1990.

Then he offered three factors contributing to the neglect of these hills: “We failed to build the settlements in urban hilly areas, nor could we modernize farming, the mainstay of hill economy,” he said. So the hill men began to migrate to Tarai plains so that they could have enough to eat.

The second factor, he argues, is state actors’ inability to translate development vision for the hills into action. “Hills’ development remained limited to a political slogan. So far no leader has been guided by the drive to develop the hills. Their effort is limited to bringing one or two projects into their constituencies. That’s all.”

Adhikari mentioned the third factor which is rarely ascribed to hills’ sorrows: the excuse of ‘geopolitical constraints’. If we had built the north-south highway and diversified our access with the northern neighbor after 1990, Nepal’s hills and mountains would witness greater developments, he said. “Indian economic blockade prompted the leaders to pay more attention to the need of north-south highways. But had you heard them talk about it before the blockade?” he asked.

There is another aspect to it as well. Rulers of this country have used the hills (read: hill people battling miseries and hardships) to serve their interests. The Rana rulers did so until 1950. After 1990, the political class started to send hill people to the Middle East and the Gulf instead of engaging them back at home. After 2006, the key goal of hill leaders has been pleasing various power centers. They have stopped becoming accountable to their own people.

This matters. Nepal’s anti-hill lobby is right about one thing: hill folks are nationalist, sometimes more nationalist than others because nationalism is in their blood. If you empty the hills by sending the able-bodied youth outside the country, you don’t have to bother about hills. One great benefit of this for the rulers will be that when they push the country to the brink, those who love the country the most will not be there to stop them.

But this indifference cannot go on for long. It is not in the nature of the hills to remain silent. They will speak. Those who claim to represent the hills will have to listen. Hills will have to be recognized for sustaining the country thus far.

mahabirpaudyal@gmail.com

You May Like This

Tale of neglect

Government response on reconstruction ... Read More...

Ethnic parties in eastern hills lose election deposits in their own strongholds

ILAM, July 12: Ethnicity-based fringe parties, which have their stronghold in the eastern hill districts, have lost their election deposits in... Read More...

Chhath festival in the hills

DHADING, Nov 6: Chhath festival, normally celebrated in the Tarai or plains of the country is gradually becoming an occasion... Read More...

Related News

Just In

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

- WB to take financial management lead for proposed Upper Arun Project

- Power supply to be affected in parts of Kathmandu Valley today as NEA expedites repair works

- Godepani welcomes over 31,000 foreign tourists in a year

- Private sector leads hydropower generation over government

- Weather expected to be mainly fair in most parts of the country today

- 120 snow leopards found in Dolpa, survey result reveals

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment