OR

Traffic Police attribute 90 percent of all road accidents in Nepal to transport syndicates

On August 15, a 35-seater bus carrying around 90 passengers, and goods, veered off the road at Birtadeurali VDC in Kavre district, killing 27 and injuring 43 others. This was one of the deadliest road accidents in Nepali history and yet it couldn’t grab as much attention as the news of air crashes. This is because it is the poor who suffer disproportionately in road accidents. So even though an average of five people die in road accidents in Nepal every day, it is still a neglected topic.

According to Nepal Police there has been a gradual rise in the number of road accidents as well as the number of fatalities. In the fiscal 2013/14 there were 8,406 road accidents across the country and 1,787 people lost their lives.

Coming to the fiscal 2015/16, there were 10,013 accidents, with 2006 people dying. In past one month alone more than 115 people have been killed while over 250 others were severely injured in our roads across the country.

The World Health Organization (WHO) dubs road accidents a “hidden epidemic” as 1.3 million people around the world die from them every year, with more than 90 percent victims coming from poor and middle income countries like Nepal.

Road accidents were the ninth leading cause of death in 2004 and could be the fifth by 2030, according to the WHO. In an attempt to make our roads less dangerous, the WHO in 2011 launched a “decade of road safety” with a plan to save five million lives and prevent 10 times as many serious injuries by 2020. As other countries are working to make their roads safer, now is time for Nepal to also look to minimize road hazards.

When road accidents claim 2,000-2,500 lives annually, the government should work with urgency to tackle them. But that is sadly not the case here. According to a report prepared by traffic police, 90 percent of our road accidents can be attributed to the syndicates in Nepal’s transport system, even though law bans such syndicates. For instance the Competition Promotion and Market Protection Act 2006 bans all forms of anticompetitive practices and behaviors, but transport agencies openly run syndicates as it is they who decide route permits and transport fares. They even bar the entry of new players in the field.

A case in point is the fiasco between the Sudur Pashim Yatayat and the recently launched Badimalika Yatayat. As Badimalika started operating deluxe buses, with competitive fares, on the Dhangadhi-Kathmandu route, transport entrepreneurs affiliated with Sudur Pashim resorted to vandalism of Badimalika buses. Such was also the case when Sajha and Mahanagar Yatayat started plying their new buses in Kathmandu to ease commuters’ woes. Nearly all major road routes in the country are controlled by these syndicates, who effectively run a parallel government. They continue to flourish even though the Supreme Court has banned them. This is because there is a close nexus between our top government officials and the operators of these syndicates. Moreover, many politicians have invested in the lucrative transport sector.

There is also the Motor Vehicles and Transport Management Act (1993), which has clear provisions related to road safety, fares, overloading and driver shifts. But almost all these provisions are conveniently overlooked. The transport syndicates can do so as they have political backing.

Apart from cracking a whip on these syndicates, the government should also introduce stringent laws for those who violate traffic rules and it should invest in raising public awareness. But that again does not seem to be a priority. Thus even though the traffic police has repeatedly requested the Ministry of Education to include road safety in school-level curriculum, their pleas have fallen on deaf ears. Likewise, the cabinet two years ago approved new driving license provisions for public vehicles, but they once again could not be implemented due to protests from transport entrepreneurs. If the provisions had been implemented, a public-vehicle driver would need to be at least 25 and he/she would need to undergo three years of training after obtaining license, before he/she was allowed to drive public vehicles.

But these provisions too remain limited to paper.

There are many other measures with which we can make our roads safer, for instance by controlling drunk-driving on longer routes and improving our emergency services in order to minimize fatalities. The total estimated annual loss due to road accidents comes to around 0.5 percent of the national GDP. This isn’t surprising since many breadwinners are badly maimed or killed in road accidents. Hope this issue soon gets the serious attention it deserves.

dk7030@gmail.com

You May Like This

SC orders roads dept to leave Limbu sacred stones untouched

KATHMANDU, OCT 26: The Supreme Court on Wednesday issued a certiorari order directing the government authorities to avoid the sacred stones,... Read More...

Thousands left stranded as Khotang roads remain obstructed for four days

KHOTANG, Jan 11: Thousands of commuters have been left stranded in Khotang due to the locals' protest against decision of the... Read More...

Police nab ‘serial killer’ Chaurasiya

RAUTAHAT, Aug 26: Notorious serial killer Balkishor Chaurasiya, who was arrested on the charge of kidnapping and murdering a minor... Read More...

Just In

- 80 civil servants left in the lurch as MoFAGA places them in reserve pool

- Weather Alert: Storm likely in Lumbini and Sudurpaschim

- NOC investing Rs 3 billion to construct fuel storage plants of over 9,000 kl capacities in Bhairahawa

- Reflecting on a festive journey filled with memories and growth

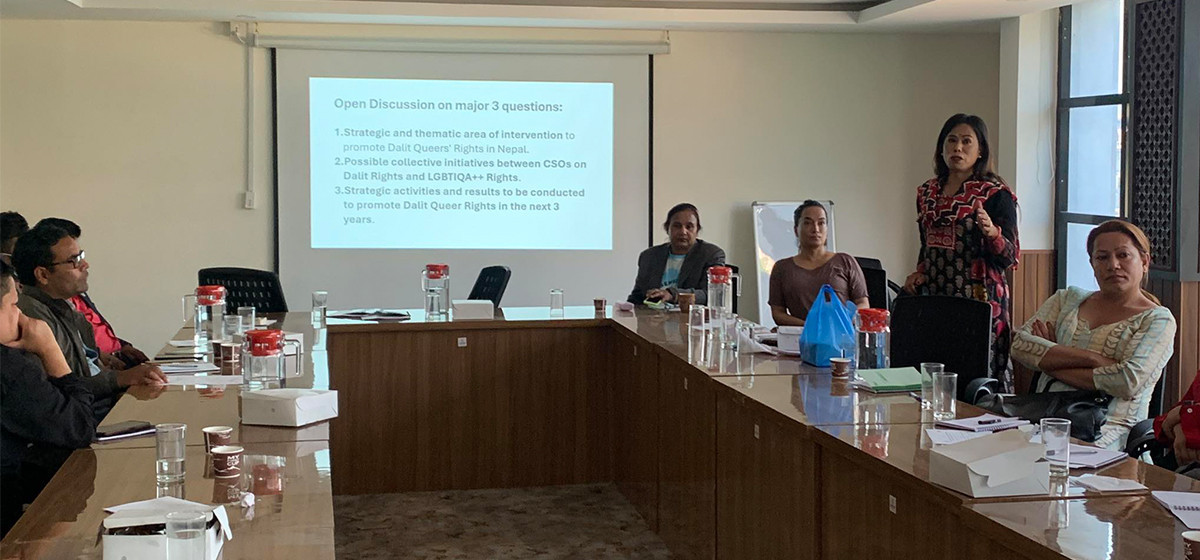

- Dalit sexual and gender minorities lack representation within their own communities and groups

- Nagdhunga-Sisnekhola tunnel breakthrough: Beginning of a new era in Nepal’s development endeavors

- Altitude sickness deaths increasing in Mustang

- Weather forecast bulletin to cover predictions for a week

Leave A Comment