OR

High interest regime

Banking, like every other sector of the economy, operates on the principle of demand and supply. When the market is flush with money, the demand for it is low, which is reflected in the low interest rates that banks offer against the deposits, both personal and institutional, they mobilize. Nepali banks, swimming in remittance money, have been offering ultra-low interest rates to their depositors. With official inflation running at around 10 percent, but the banks willing to pay just 1-3 percent on deposits, the folks who like to keep their cash in the banks have seen progressive devaluation of their deposits. Even fixed-account yearly deposits these days fetch a measly 3.5-4 percent. But things could be about to change. In the first month and a half of the current fiscal, the loan disbursements of commercial banks surpassed their deposit mobilization, the first time that has happened since the promulgation of the new constitution in September, 2015. The earthquakes, soon followed by over four months of border blockade, together had a devastating impact on the banks’ loan books. In the uncertain political and economic climate that followed, few people were willing to borrow money from the banks and invest.

But with the end of the blockade at the start of February this year, people have shown greater willingness to make investments. At the same time, remittance inflow has stabilized, following years of rapid growth. With most of the government money locked up inside the coffers of the central bank as a result of low capital expenditure, another important source of money in the market has also dried up. In other words, years of remittance-fueled liquidity might be coming to an end. The commercial banks are already offering interest rates of up to 6 percent on one-year deposits, to shore up money just in case. While this may be good news for depositors, it is not necessarily so for the economy as a whole. Banks offering their customers good rates is beneficial to the economy only if it’s the result of free competition among commercial banks: the healthier the economy, the greater the competition. But this is clearly not the case in Nepal. Here the interest rates are largely driven by external factors like remittance, not the strength of the national economy as such.

But in a booming economy people won’t look to park excess cash in the bank, and certainly not for the interest rate on offer, since there are many other, more lucrative avenues of investment. The high-income earners, secure in the health of the economy and their future earnings, also spend more. This money in turn circulates through the banking system.

Thus, in the end, all sections of the society benefit. But excessive focus on bank interest, as is the case in Nepal, suggest that people are still unsure about investing, and are still heavily reliant on banks to park their excess cash. Be it in the coffers of the central banks or in the vaults of the commercial banks, either way a huge amount of money that could otherwise have been put to good use is still sitting idle. Unless this cash is put to work, not many folks in Nepal will be making any serious money.

You May Like This

Pandora’s box

If all the old disputes remain alive and nothing changed over the past 12 months, is there anything at all... Read More...

Netflix will cut ‘Bird Box’ footage months after outcry

Netflix will remove footage of a real fiery train disaster from its hit post-apocalyptic survival film “Bird Box” months after... Read More...

'Wonder Woman' dominating box office, leaves 'The Mummy' in dust

Wonder Woman, the muscular feminist superhero from Warner Bros. and DC Comics, stayed strong over the weekend, easily holding onto... Read More...

Just In

- Partly cloudy weather likely in hilly region, other parts of country to remain clear

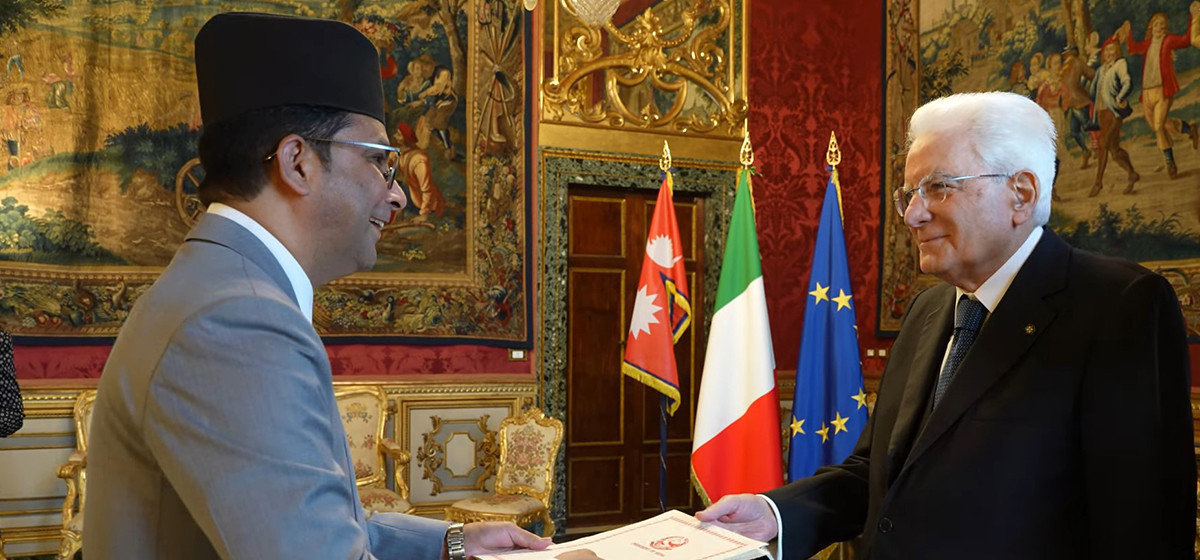

- Nepal’s Non-resident Ambassador to Italy presents Letter of credence to President of Italy

- 104 houses gutted in fire in Matihani (With Photos)

- By-elections: Silence period starts from today, campaigning prohibited

- A Room of One's Own- Creative Writing Workshop for Queer Youth

- Tattva Farms rejuvenates Nepali kitchens with flavored jaggery

- Evidence-Based Policy Making in Nepal: Challenges and the Way Forward

- Insurers stop settling insurance claims after they fail to get subsidies from government

Leave A Comment