OR

Sidelines

Similar to the dominance of Chakari and Afno-manchhe beneficiaries of Khas-Arya elites in Nepal, the Siamese of Thailand dominate the State

When Bhumibol Adulyadej, 88, died on October 13th after spending better part of the last decade in an infirmary, superlatives began to fly thick and fast. Reverential obituaries, perhaps written well in advance and kept ready for release at the appropriate time, were padded up and immediately produced. What adds lustre to the legend is that most such characterizations of the Siamese king are indeed true.

Bhumibol was the richest sovereign in the world with a fortune estimated—the tax-exempt Crown Property Bureau doesn’t have to publicize its assets or income—to be anywhere between 40 and 60 billion dollars. With 70 years on the gilded throne, he has been the longest reigning monarch in history since the Sun King Louis XIV of France. A headline writer of the venerable The New York Times called him the “King of the People”, as if it’s possible to be the ruler of anything else. The Economist noted that he “lived through 26 prime ministers, 19 constitutions and 15 coup attempts, nine successful” without caring to explore in detail whether the king had some role to play in all those upheavals. The king indeed was a darling of the media.

Divinity is routinely ascribed to most ruling dynasties, either as personification of the Supreme or his most faithful and chosen representative on earth. The Thai King epitomizes a unique blend of Hindu and Buddhist myths. He is the Rama, the virtuous God-king of Ramayana in Hindu mythology, and yet the most devout Buddhist engaged in worldly duties in pursuit of nirvana.

The Rama IX of the Chakri Dynasty, which boasts of the thunderous trident (Trishul) of Mahesh protruding out of Vishnu’s celestial discus (Chakra) as its coat of arms, held power and influence far beyond the imagination of most rulers and yet succeeded in maintaining the image of a monkish monarch reluctant to exercise his authority. The national emblem of Thailand is a Garuda, the mythological bird that acted as the vehicle of Vishnu. The relationship between the two motifs is suggestive.

Born in the US—allusion to the celebrated Bruce Springsteen track appears uncanny since the Thai ruler remained a pillar of strength for his country of birth throughout the Cold War—and educated in Europe, Bhumibol became the cultural emblem of the Siamese only after the Chakri Crown fell by accidental design upon his head. When his German-born brother and Rama VIII of Siam since an early age was found unexplainably shot dead in his bedroom in June 1946, Bhumibol was put forward to bear the burden of Mandate of Heaven. Draconian lèse-majesté laws of Thailand have precluded wanton wagging of tongues, but the resourceful palace secretariat had to resort to the desperate measure of sending a few of its minions to the gallows to cover up the regicide.

Heavenly mandate

Like so many lore and legends related to hierarchy and order in society, the doctrine of Mandate of Heaven too was born during the 800-year long Zhou Dynasty (1045 BC to 256 BC) in China. It’s merely a phrase to legitimize the usurpation of power by new claimants.

The virtue of the ruler is clearly an afterthought. Ironically, it took protestors of the Tiananmen Square in 1989, who had been claiming that the Chinese Communist Party had lost the mandate of heaven to rule, a brutal suppression to realize that like power, its divine legitimation too flowed from the barrel of the gun.

Whatever may have been the circumstances of his enthronement, Bhumibol did everything under his command to earn the title of Father of the Thai Nation. His birthday is the National Day of Thailand and the National Father’s Day. Quite naturally, the National Mother’s Day falls on the birthday of the Queen. Mendicants and monks realize pretty soon that manufacturing legends to legitimize the monarchy has its advantages. Since they are the ones to set and maintain social values, all rulers with absolutist ambitions leave no stone unturned to earn the unquestioned loyalty of priests and clerics. Perhaps it was not so very difficult for the Siamese monarch to convince the Buddhist clergy that he was their best hope against militarism and modernity.

The second and an equally sturdy pillar of the platform upon which the Crown usually glistens unchallenged in its primacy is the military of the country. Having never fought a major war since the Burmese-Siamese showdown of the 1780s, the Thai army of the 1950s was an instrument that the Allies and the Axis powers had used alternately according to their convenience. It was easy for the monarch to play with internal contradictions between military brasses and make them compete with each other in earning and keeping the royal patronage. The success or failure of frequent military coups in Thailand depends upon predilections of the royal palace.

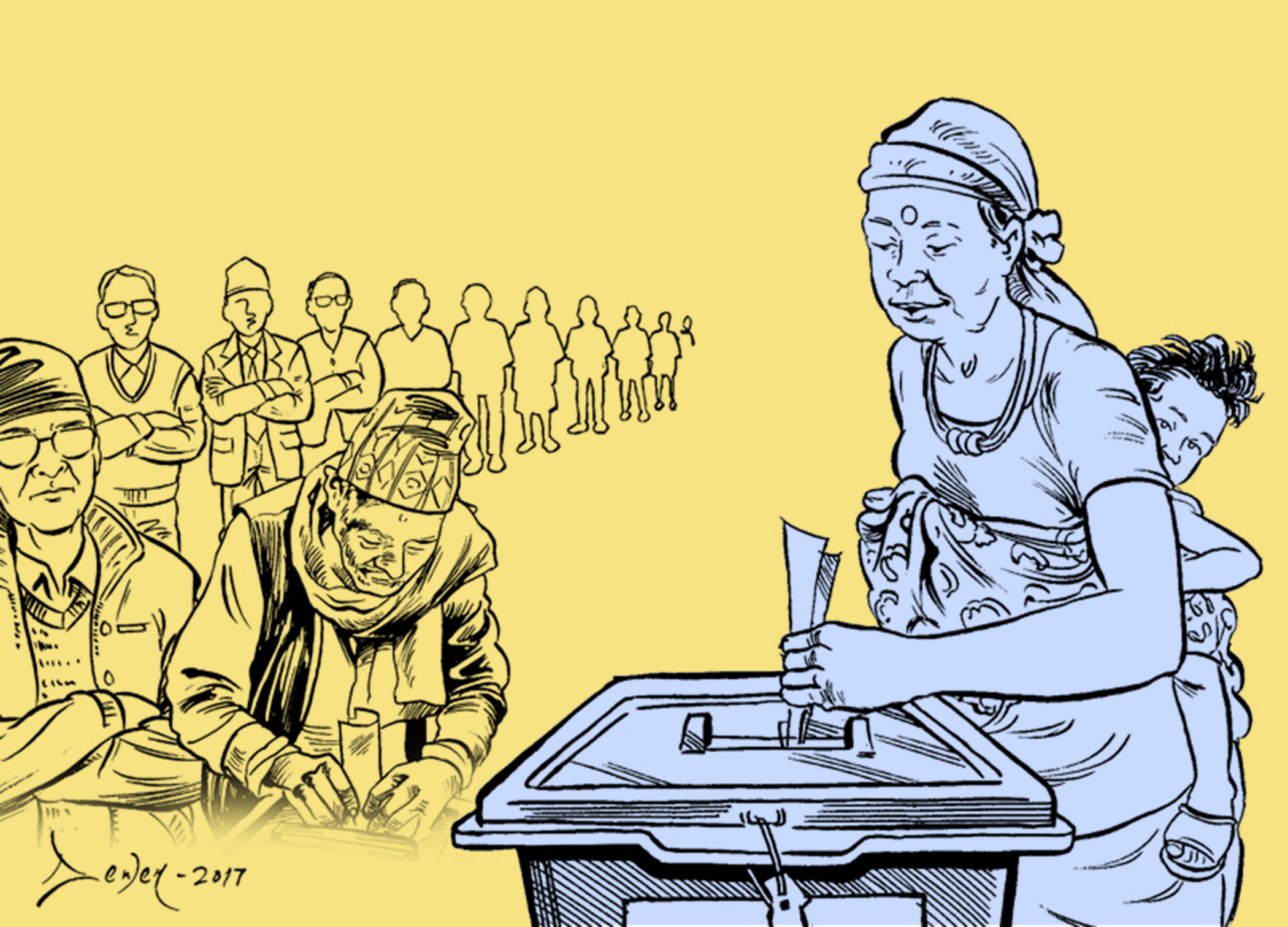

After the modernization drives of Chulalonkorn Rama V, the emergence of powerful bureaucratic elites had began to replace whimsies of feudal lords, royal relatives, and other sundry aristocrats. The investment in creation of meritocratic mandarins has paid handsome returns. Somewhat similar to the dominance of Chakari (cultivation) and Afno-manchhe (patronage) beneficiaries of Khas-Arya elites from the mid-mountains in Nepal, the Siamese of central Thailand dominate the State in collaboration with coreligionist monks and a military establishment that largely comes from the same community. The relationship between bureaucratic mandarins and the monarchy is mutually advantageous. The third pillar supporting the myth of God-king got strengthened during the reign of Rama IX.

Merchants may not appear powerful in public, but they are the ones that have to carry the weight of exploitative elites everywhere. This is where conflicts often arose between the old-school Chinese-Thais businesses and the upstart Siamese entrepreneurs. A direct link is impossible to establish, but perhaps the ethnicity of the Sinawatra clan has something to do with the fact that repeated military coups have been necessary to keep the family that has won every election of the noughties out of political power. Since Siamese businesses have benefited immensely from their links with the military and the mandarin establishment, they perhaps fear that the marriage of merchant influence and popular politics can emerge as a formidable challenge to their hegemony. But Thailand being what it is, even talking about one’s ethnicity is taboo and everyone is required to acquire a proper Thai-sounding name to camouflage her cultural roots.

In addition to the military, monks, mandarins and merchants, what really kept the Thai monarchy propped up for seven long decades was the unflinching backing of the US Marines. Fearing communist spillover from Indo-China, the US turned Thailand into the Rest and Recreation center of its forces. The anti-communist campaigns in the ASEAN region, many of them with a racial tinge directed against the ethnic Chinese, were often conducted and coordinated from Thai bases. Tourism boomed. Economy picked up. But society largely remained in suspended animation as the military ruled in the name of the monarch. Paul Handley correctly summarizes in his The New York Times op-ed that the Rama IX has left “Thailand, as well as his heir, in the same situation he inherited all those years ago: in the hands of corrupt and shortsighted generals who rule however they want.” With the ASEAN turning into a theater of US Pivot Asia and China’s Peripheral Diplomacy contestations, that reality is unlikely to change.

Hellish angels

It may sound counter-intuitive, but the idea of constitutional monarchy is in fact a fiction of British imagination (mea culpa: I subscribed to the faith for far too long!) where traditions function in the name of the constitution. Monarchies are bound by the statute only when the supreme institution is completely divorced from other instruments of the state such as the army, the bureaucracy, and the courts that run the society and the political economy.

It’s extremely difficult to do so when absolute monarchs are like pawns on geopolitical chessboards. Perhaps longevity of the Sheikdoms of West Asia has more to do with the American interest than Islamic beliefs that actually put little value upon nobility of birth.

Despite his unsavory reputation, Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn will probably end up being the King Rama X. The alternative could be worse. Will he be able to rule? To take liberty with an old song of the newly crowned Nobel Laureate of literature Bob Dylan: The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind / of South China Sea!

You May Like This

Court verdict disrespected people's mandate: UML

The main opposition CPN-UML has concluded that the Supreme Court's decision to conduct re-election in Bharatpur Metropolitan City Ward No... Read More...

The constitution should be amended only after a fresh electoral mandate

Inclusion has been enshrined as a fundamental right. A Nepali can file a writ at the court if the state... Read More...

Just In

- World Malaria Day: Foreign returnees more susceptible to the vector-borne disease

- MoEST seeks EC’s help in identifying teachers linked to political parties

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

Leave A Comment