OR

No solution in sight

Published On: November 17, 2016 12:35 AM NPT By: Mahabir Paudyal | @mahabirpaudyal

The argument that naturalized citizens by marriage be treated as ‘special’ is fraught as we are dealing with people of two different countries

In a surprising turn, Madheshi Morcha has given Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal two more weeks to sort out contentious issues and table the constitution amendment proposal in the parliament. This, we have been told, has been done to garner support from ruling as well as opposition parties to build consensus on disputed issues of citizenship and provincial demarcations. Predictably, Morcha came down to these two crucial points from their earlier 11-point and 26-point demands, which had also included broad range of governance, accountability and transparency issues. So will the deadlock between Morcha and Big Three parties be broken in the next two weeks? Unlikely.

In fact, these issues could prove to be pain in the neck of the parties again and are likely to stall the vital constitution amendment and implementation process.

To begin with, there is a big Indian concern. India’s stand on Nepal’s constitution has not changed a bit even after it helped install Prachanda in Singha Durbar three months ago.

‘Take all actors on board before implementing the constitution,’ has been its rallying cry.

It reiterated this stand during Prachanda’s Delhi visit in September and during President Mukherjee’s visit to Nepal early this month. The official stand of India has been ‘make constitution inclusive and acceptable’ but from what has come out in Indian media in the past one year it can be safely said India wants Nepali actors to lift the constitutional restriction on naturalized citizens (of Indian descent) from reaching top posts, create two only Madhesh provinces in Tarai plains and ensure representation of Madheshis in the upper house on population basis. As is the case, the first two are nearly impossible demands.

Some Madheshi leaders have been saying they are not in favor of naturalized citizens holding top executive posts. But others, including Madheshi intellectuals, have made it a key demand perhaps because this rather emotional issue can be tweaked to make Madheshi people feel they have been disenfranchised by the constitution.

The arguments in favor of allowing naturalized citizens to hold top political posts are worth noting. Interim Constitution had not placed such restrictions on naturalized citizens, so why did the new constitution do so? They ask. True, the interim charter had stated “citizen of Nepal either by descent or birth” or “a naturalized citizen who has lived in Nepal at least for ten years” will be eligible for appointment in constitutional positions. The same provision is there in Article 289 of the new constitution as well. It only bars them from top executive, security and judiciary posts.

So what is the problem? I asked constitutional lawyer Bhimarjun Acharya. “The Interim Constitution had not defined the constitutional positions. But even then it did not mean a naturalized citizen will be eligible for the top posts like President and Prime Minister,” he said. “The new constitution has clearly defined the constitutional positions in Article 306.”

There is no bar on naturalized citizens from being appointed chiefs of constitutional bodies.

By naturalized citizens we do not mean any naturalized citizens but naturalized citizens by marriage, Madheshi leaders and supporters say.

The socio-cultural realities of Madhesh are very different from that of hills and the valley.

Since Madheshis have roti beti relations with India, the Indian women married to Madheshi men become naturalized citizens and it would be unfair to prevent them from reaching top posts. And it is unfair to question the intention of such citizens especially when they have severed ties with their homeland and chosen to live in husbands’ country. Point taken.

But there is another side to it as well. When you allow naturalized citizens by marriage to occupy top posts, and if you lift the provision of permanent residency of certain years in Nepal, you have to do so in case of all naturalized citizens by marriage, irrespective of their country of origin. If you address the demands of one section of community, you cannot deny the same to other sections. Perhaps to avoid such a bottomless pit, countries put certain conditions on their new citizens. Thus the argument that naturalized citizens by marriage (coming from India) should be treated as ‘special’ is fraught with controversy because however close to India Madhesh may be and whatever the extent of roti beti relation Madhesh may have with bordering towns of India, they are two different countries.

The syllogism that I love my wife/husband, wherever s/he comes from, s/he has become Nepali citizen, s/he is honest and loves this country and therefore s/he should be allowed to become the chief minister/prime minister of my country makes a perfect emotional appeal but if a country makes emotional appeal a benchmark to choose its chief ministers and prime ministers, why do we need a citizenship law?

One can endlessly debate this issue but unless we all agree on a uniform and internationally accepted standard on rights and powers of naturalized citizens, it is not going to be resolved any time soon. The more you push it, the more suspicion it will breed among other communities as to on whose behest such a demand is being raised in Nepal.

As for provincial demarcation, it has ceased to become a matter of public interest. As a matter of fact, the very agenda of federalism has come to mean another recipe for perennial instability. The public distaste of federalism will become even more intense in the days to come.

Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal has floated a proposal of readjusting certain districts to address boundary dispute. Dahal has proposed to move Rolpa and Pyuthan from Province 5 to Province 6. But this will make Province 6 disproportionately large. He intends to move Arghakhanchi, Gulmi and Palpa from province 5 to Province 4. This will make Province 4 too large and will deny it an access to the southern border. The economic blockade of last year has made it clear to all how crucial it is for provinces to have a direct access with India’s border. He also proposes to create a separate province by incorporating Banke, Bardiya, Kapilvastu, Rupandehi and parts of Nawalparasi.

Dispute has already emerged within Maoist and other parties over this proposal. It will flare out in the days to come. Any amendment to constitution must be acceptable to us, Morcha leaders have warned. It must be acceptable to us too, others have started demanding. Provincial disputes can only be deferred for it has raised more fear than promise of prosperous future.

Those who remind leaders of these intricacies are often at the receiving end of criticisms these days. Anyone speaking for hill-plain integration and against allowing naturalized citizens to hold the top executive posts is called regressive, hollow nationalist, anti-Madheshi, anti-Indian, ignorant, insane and conservative. Perhaps to escape such vitriol, many do limit their arguments to ‘constitution should be made acceptable to all and it should be amended on consensus’ rhetoric. The hard truth is that this is not going to happen.

A constitution crisis is almost inevitable. The much-hyped local elections scheduled for March/April next year won’t take place. We will not have three sets of elections before January, 2018. The Big Three parties will then agree on amending the constitution to extend the deadline for constitution implementation. Post-earthquake reconstruction won’t gain pace. The misuse of state funds will go unabated. If Madheshi forces consider the dangers all this will lead the country to, the crisis can be averted. But as things stand they seem to be waiting for the time when they can say: Look, what happens when you don’t do what we say.

Twitter: @mahabirpaudyal

You May Like This

Resignation of party leadership no solution: NC General Secretary Koirala

CHITWAN, Dec 13: Nepali Congress (NC) general secretary Dr Shanshanka Koirala has said resignation of the party leadership is not... Read More...

Federer and Nadal move within sight of landmark meeting

NEW YORK, September 5: Roger Federer crushed Germany’s Philipp Kohlschreiber 6-4 6-2 7-5 to ease into the quarter-finals of the... Read More...

The solar solution

Now that NEA has amazingly reduced load-shedding, PV modules are like expensive clothes hung to dry ... Read More...

Just In

- Rainbow tourism int'l conference kicks off

- Over 200,000 devotees throng Maha Kumbha Mela at Barahakshetra

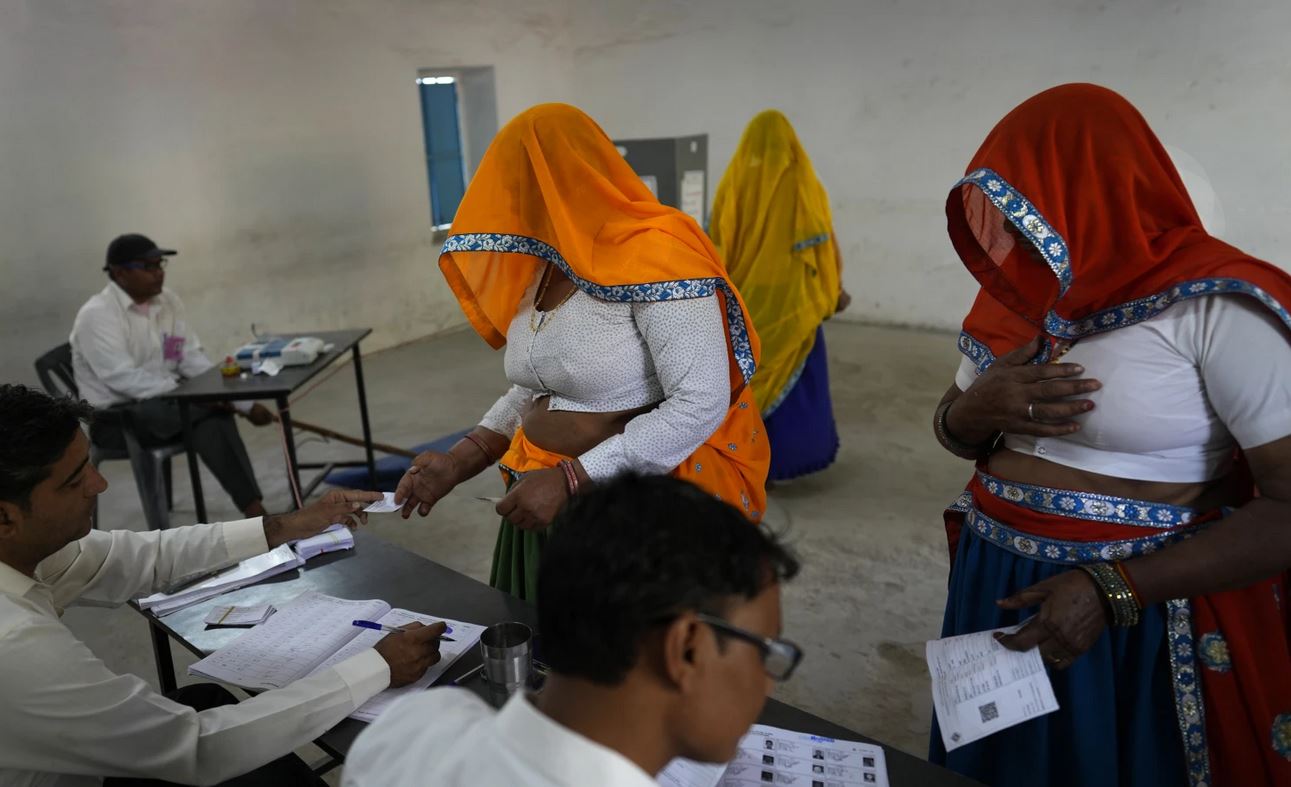

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment