OR

Kaushik Basu has proposed that the law be amended to reflect that giving bribe is legal but taking it is not

On November 8th, Narendra Modi suddenly banned the 500 and 1,000 rupee Indian notes, and in the process popularized a word not many had heard before: demonetization.

Modi stated that this action was a response to endemic corruption and black money in India. The logic is that black money in India is hidden under mattresses in 500 and 1,000 rupee denominations. Modi thinks that banning the large denomination notes will render all that black money useless. However, 86 percent of India’s cash is stored in 500 and 1,000 denominations. Also, much of India engages in cash transactions. So it is not only the rich who have suffered from the ensuing chaos. Around 50 demonetization-related suicides have been documented in India so far. Not one of those 50 appears to be rich.

So how corrupt is India? For the year 2015, Transparency International’s “Corruption Perceptions Index” ranked India 80 in the world among the 168 surveyed countries. In South Asia, India fared better than Nepal (85), Sri Lanka (90), and Afghanistan (166), but worse than Bhutan (27) and Bangladesh (68). The Maldives and Pakistan were not surveyed. So India is in the middle of the pack in both the world and South Asian rankings.

While many Indians have lost their lives due to post-demonetization chaos, many support the initiative. To gauge the public’s reaction, Modi launched the NaMo app to collect the public’s vote. The results so far indicate that 93 percent of those that voted through that app approve of their prime minister’s action. However, only 500,000 people have voted so far, and chances are high that the majority are BJP stalwarts who would blindly support just about any crazy idea that Modi can conjure up.

Analysis and statistics will tell us in the future whether Modi’s demonetization action was a master-stroke or a dud. But the policy is fraught with dangers.

There is a perception that the anti-corruption drive in India is a partial success at best.

Arvind Kejriwal—the Aam Aadmi Party leader—and others have accused Modi of informing his friends of the ban beforehand. While that is difficult to prove, it is far easier to establish that 1,000 rupee Indian notes were being bought by smart “entrepreneurs” for much less in parts of Nepal. If that is happening in Nepal, I can only imagine what is happening in India, mostly rural India where people have no access to banks. The opportunists have suddenly become rich due to Modi’s scheme.

Many people in other countries will suffer, too, as a result of this ban. There are millions of Indians all over the world who keep a certain amount of these large denomination notes with them. I have personally spoken to three of my Indian friends who live outside India, and they mention they each have around IRs 15,000-20,000 with them in 500 and 1,000 denominations. That money comes in handy every time they visit India. How many billions worth of 500 and 1,000 rupee notes that Indians living abroad hold are now suddenly worth nothing. Nobody knows.

This is a spectacular policy failure, especially because India wants to become a world economic power. It wants its currency to be traded worldwide, like the US dollar and the Euro. It even came up with a new symbol for the Indian rupee with that purpose. However, Modi’s demonetization scheme just crushed that ambition. Can anyone ever imagine the United States suddenly deciding to ban all their 100 dollar bills? That would lead to a collapse of the world economy. Thankfully, India is not the United States and the world economy is safe despite the demonetization folly. However, the demonetization also means the Indian rupee is nowhere close to becoming an internationally traded currency.

Even if the demonetization scheme achieves its purpose this time, who is to say corruption in India will not continue in the future? What if the new 500 and 2,000 rupee notes do not curb but instead abet corruption? Will India, then, issue 500 and 3,000 rupee denominated notes?

The Indian government—in fact, all governments—need to understand that corruption exists because of other policy failures. For example, the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988 considers both bribe-taker and bribe-payer in India equally guilty and both receive equal punishment under the law. That clearly goes against the intent of the Act to reduce corruption because a bribe would never be reported because both the sides stand to lose from the revelation. Other legislations, such as those that deal with bank and securities fraud, grant amnesty from prosecution to those who expose such frauds. However, the Indian law’s unclear language on amnesty and the onerous onus it places on the accusers has resulted in toothless action.

Kaushik Basu, the noted Indian economist, has been arguing for clear amnesty language for decades. He has proposed that the language of the law be amended to reflect that giving bribe is legal but taking it is not. In addition, if it is proven that bribery has taken place, the person receiving the bribe would not only have to suffer legal consequences but also return the amount of the bribe to the briber payer. Basu argues that this would ensure the interests of the bribe payer and receiver are not aligned. Once the bribe is paid, the payer would have all the incentives to expose the bribe receiver.

Every corrupt country has to start somewhere to tackle the problem. India—as well as its poorly ranked neighbors—would be wise to give Basu’s ideas a chance. It is a more sensible policy, it won’t lead to a crash of the global economy, and it will not make the poor commit suicides.

Twitter: @khanal_m

You May Like This

PM commits to wiping out corruption, irregularities

KATHMANDU, July 28: Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli has said the government was active enough to ensure the rule of... Read More...

A year of corruption scams, impeachment bids

The year 2017 was marked by a series of scandals in the country. ... Read More...

Bibekshil launches an awareness program against corruption

KATHMANDU, March 5: Bibekshil Nepali Party has launched an awareness program against corruption in the area of Basantapur square, Kathmandu. ... Read More...

Just In

- 265 cottage and small industries shut down in Banke

- NEPSE lost 53.16 points, while investors lost Rs 85 billion from shares trading last week

- Rainbow tourism int'l conference kicks off

- Over 200,000 devotees throng Maha Kumbha Mela at Barahakshetra

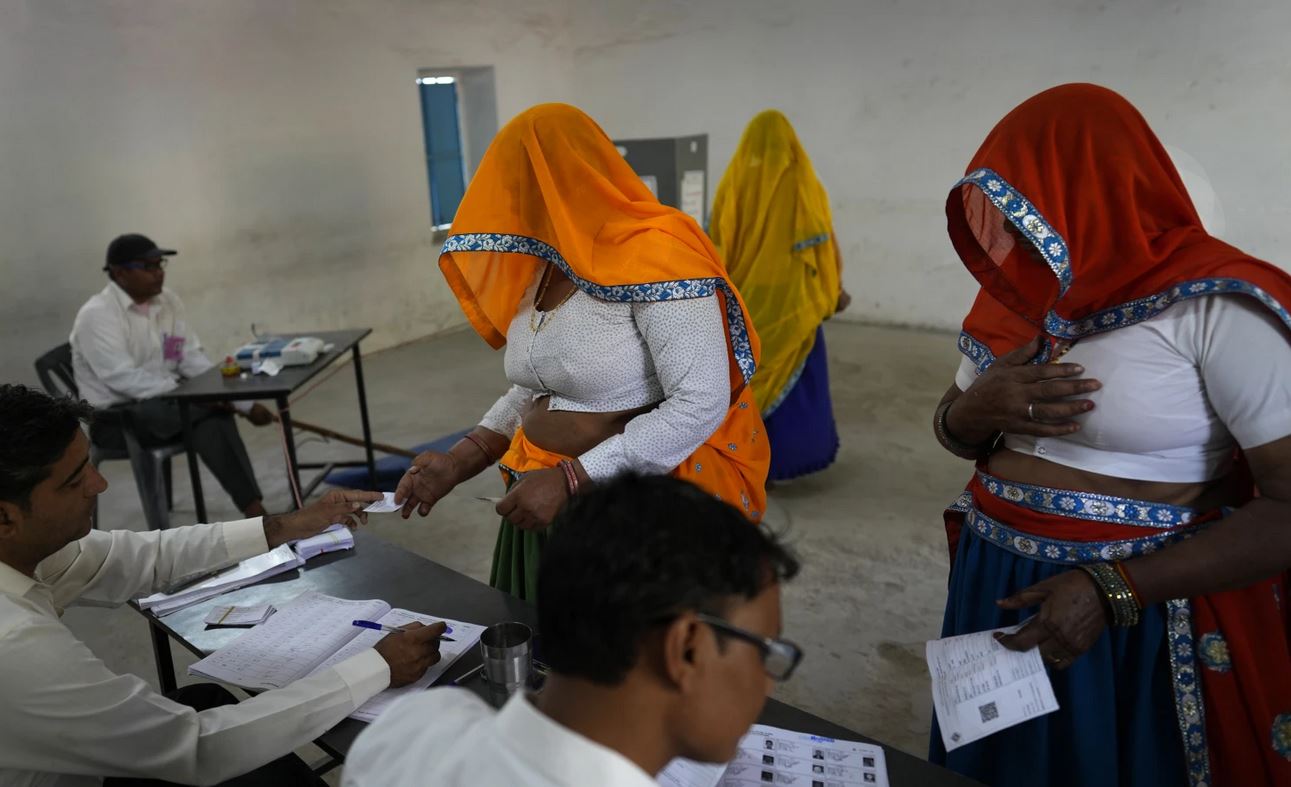

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment