OR

Mahabir Paudyal

Mahabir Paudyal is an opinion writer at Republica with interest on history, domestic politics and international relations.mahabirpaudyal@gmail.com

More from Author

- Nepal is falling into a trap of India, China and the US

- Prime Minister Oli is pushing the country to precipice. Is there a way to stop him?

- How can you be so irresponsible about education?

- What is Nepali Congress thinking about China?

- Fellow Nepalis, fear the government, fear as much for the country

Great Indian irony is that when Nepal seeks to diversify trade with China and

attract Chinese FDI, they take it as an intrusion on their area of influence

One reason Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi went to Nepal, wrote S D Muni, Professor Emeritus at Jawaharlal Nehru University, in one of his recent commentaries, is that “Modi administration had become acutely conscious that a crippled Neighborhood First was facilitating China’s strategic expansion in India’s sensitive periphery.” More such commentaries interpreting Modi’s visit as a move to counter Chinese influence in Nepal are making rounds. This is no surprise though.

Indian media and strategic thinkers show a great China premonition. Indian media was replete with commentaries during Prime Minister K P Oli’s India visit early April in which every Indian gesture toward Nepal was interpreted as a reaction against Nepal getting close to China.

So they called the April 7 deal between Nepal and India on Kathmandu-Raxaul railway as a strategy to counter Nepal-China railway. Nepal and China had agreed to start technical works to build a cross-border railway link via Tibet to boost connectivity during then Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Krishna Bahadur Mahara’s visit to Beijing in September, 2017. Modi’s invitation to Oli on the days that coincided with Boao Forum was seen as New Delhi’s deliberate attempt to prevent Oli from going to Boao.

India, it seems, is not ready to think of Nepal independently of China. Nepal, in turn, has to live with constant anxiety of how India will react if it gets close to China.

The BRI anxiety

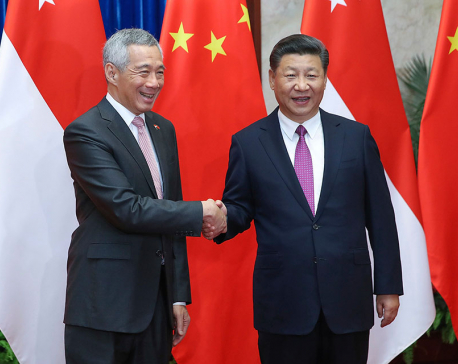

It consternated Indian thinkers when in May, 2017 Nepal signed on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) agreement with China. China seems determined to push BRI—a multibillion dollars flagship project of President Xi Jinping— irrespective of what India or any other countries think of it. India, on the other hand, casts uneasy aspersions on BRI.

India views BRI as a ploy to give strategic advantage to Pakistan—its sworn enemy. The Indian think tanks claim this is Xi Jinping’s “debt trap” project. Center for Global Development, a think-tank based in Washington, DC, made such assessment in March.

They warned that debt traps created by China through BRI would increase India’s political cost to deal with its neighboring states. It accuses China of grabbing land of smaller, less-developed countries by giving them loan on high rates for infrastructural projects, then acquiring equity into projects, and when the countries are unable to repay the loan, by getting ownership of the project and the land to use it against India.

Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is cited as the proof of how effective China’s debt-trap diplomacy under BRI can be. Some go to the extent of saying that “BRI represents the dawn of a new colonial era—the 21st-century equivalent of the East India Company.” Indians think joining BRI will entail sovereignty threat to India because BRI also includes China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which passes through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

How will Nepal select projects under BRI? How will Nepal be able to push its connectivity projects with China, while similar connectivity projects have been proposed by India as well? These are the big questions.

Understanding China

I have always wondered how much we understand China or whether we understand it at all. Surely, you cannot judge China by making a few trips there or reading a few materials in the newspapers. British journalist Martin Jacques, the author of When China Rules the World: The End of Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order offers interesting insights. He says the problem with the West is that it understands China in the western terms, using western ideas but what works in the West does not work in China.

According to him, the Chinese state enjoys more legitimacy and more authority among the Chinese than western states.

The state in China is given very special significance as the representative, the embodiment and the guardian of the Chinese civilization state. He goes on to say that the Chinese have a very different view of the state: “In the west we tend to view the state as an intruder, a stranger, whose power needs to be defined or constrained. The Chinese view the state as a head of the family, a patriarch.” Jacques’ conclusion is that we cannot understand China simply by drawing on western experience, looking at it through western eyes and using western concepts.

I wanted to find out if that is the case while in China last month during an interaction with students and professors of Leshan Normal University of Sichuan province. They think of China as a great country and President Xi as a father of the nation. If you speak critically of the president they feel offended. “How can you speak ill of our president?” One student asked. Such is a reverence for President Xi in China—something one would not find in Nepal and, for that matter India.

China has allowed its citizens to do everything—eat, drink, make merry, make money, spend and consume. But it says: Do not speak against the country and its political system because they are your guardians.

Many Chinese think of India with sympathy. India is a struggling economy with a lot of problems, one professor said. We don’t think of India as our rival, our target is to surpass the US.

It’s the economy

Forget Nepal for a moment. Facts show that India and China cannot afford to remain on bad terms. They are the biggest trading partners of each other. India received USD 1.78 billion foreign direct investment from China during April 2000 and December 2017 and the bilateral trade between the countries increased to USD 71.42 billion in 2016-17 from USD 70.17 billion in 2014/15. India and China are important engines of regional and global economic growth. Great Indian irony is that when Nepal seeks to diversify trade and attract similar Chinese FDI, they take it as an intrusion on their area of influence.

Goldman Sachs predicted few years ago that China will overtake the US as the world’s largest economy in 2026. American author Geoff Golvin argues Chinese economy will be bigger than America’s before 2030. On purchasing power category China has already surpassed the US.

How should we deal with such China? How should the world live with such China? Associate Professor at Tribhuvan University’s Master’s Program in International Relations and Diplomacy Khadga KC has some definite prescriptions. “The world should better respond to China peacefully and cordially because China is not coming up aggressively or militarily,” he argues.

“Since India and China are at loggerheads over border issues and have fought war, India naturally sees China as a strategic rival in the region. But they have more than 80 billion dollar trade and India has huge trade deficit with China. Thus there is no alternative for India to engage with China economically leaving aside other differences,” KC further explained.

The same goes with the West in his view. “The West should also take China as promising trade partner instead of potential strategic threat.” The developing world can learn a lot from China’s experience in infrastructure development, poverty alleviation and trade promotion through Foreign Direct Investment, he said.

KC believes Nepal can benefit from China’s rise through “BRI projects.” “Nepal can build rail and road link, telecommunication, energy transmission and gas pipeline with China which may diversify our trade, reduce trade deficit with other countries and downsize our asymmetric dependency on access to sea solely through India,” he said.

Truth be told

We need to identify truth and falsity in claims and counterclaims on BRI. If BRI or any other initiative towards trans-Himalayan cooperation pose challenge to the countries involved in the process, what kind of challenges are they? How genuine is Indian perception that CPEC poses threat to its sovereignty? What is China’s view on debt trap?

In an interview with The Hindu before he left for New Delhi early April, Nepali Prime Minister was asked about Nepal’s risk of falling into BRI debt trap. Oli dismissed it. “I object to the use of the word “trap.” That is a word from Indian perception and reflects the rivalry of [India and China],” he said. Nepal seems confident that there will be nothing like ‘debt trap’ for Nepal.

The West and India may devise their strategies to deal with rising China in their own way. For Nepal, for which connectivity and greater engagement with China is a compulsion rather than a choice, it is important to engage with China profitably and productively. No small order for Nepal.

Twitter: @mahabirpaudyal

You May Like This

In China, foreign minister Gyawali dreams to travel in China by modern train

BEIJING, April 18: Nepal is a natural area for cooperation between China and India, the Chinese government’s top diplomat State... Read More...

China protests US Navy sailing near South China Sea claims

BEIJING, Oct 11: China is protesting the sailing of a U.S. Navy ship near its territorial claims in the South China... Read More...

Just In

- Khatiwada appointed as vice chairman of Gandaki Province Policy and Planning Commission

- China's economy grew 5.3% in first quarter, beating expectations

- Nepal-Bangladesh foreign office consultations taking place tomorrow

- Kathmandu once again ranked as world’s second most-polluted city

- PHC endorses Raya as Auditor General

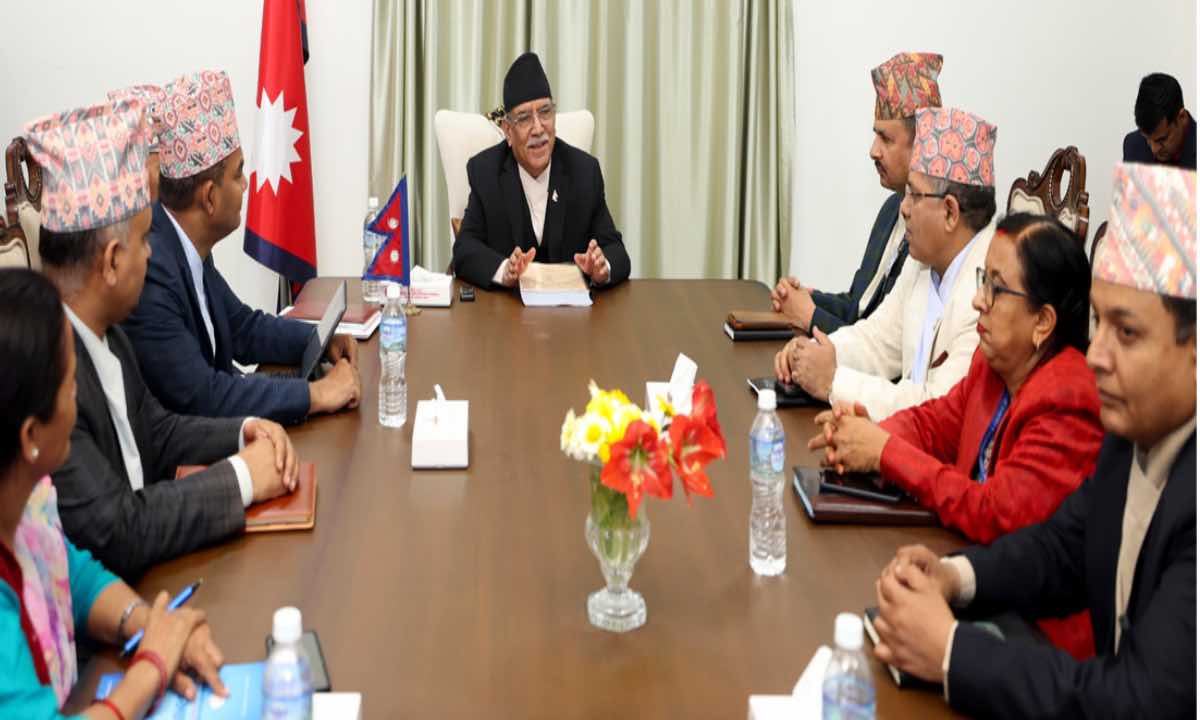

- PM Dahal and ex-PM Khanal meet

- Revised report on job specification submitted to PM

- Home ministry recommends Joshi and Dhakal for promotion to AIG

Leave A Comment