OR

Opinion

Ram Mandir Inauguration and its Ram-ifications for Nepal

Published On: January 21, 2024 09:00 AM NPT By: Mahesh Kumar Kushwaha

More from Author

The temple’s consecration ceremony in Ayodhya, the mythical birthplace of Lord Rama, has succeeded to garner an unprecedented amount of Hindu solidarity and sense of pride globally.

A few days ago, my mother called me from my father’s WhatsApp to deliver my cousins’ request: they were asking for donation to support the upcoming celebration they had organized at the local Hanumaan temple on January 22, 2024—the famous day when PM Modi of India will inaugurate Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. One of my cousins is a Swayamsevi—‘a volunteer’ trained by the Hindu Swavayamsevak Sangh (HSS), the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)’s Nepal chapter. So, it took me no time to deduce that the grand celebration in the village was organized by HSS’ younger generation of swayamsevak, mobilized by the group’s older generation, and overwhelmingly supported by the villagers.

The temple’s consecration ceremony in Ayodhya, the mythical birthplace of Lord Rama, has succeeded to garner an unprecedented amount of Hindu solidarity and sense of pride globally.

The jubilation is particularly pronounced along the southern plains of the Hindu-majority Nepal.

A delegation of some 500 Nepalis—led by Janakpur’s Manoj Kumar Sah and Janaki Temple’s deputy priest Mahant Ram Roshan Das—have already delivered about “3000 baskets of gifts, including jewellery, sweets, fruits, clothes and utensils” to Ayodhya. Local governments in the country’s Madhesh Province have gone beyond just acknowledging the event and have made calls for action. For instance, Birgunj sub-Metropolitan city, which is celebrating the occasion by installing a statue of Ram at the Ram-Janaki temple, has banned animal slaughter and the sale of meat, fish, and alcohol on that day. Similarly, Kalaiya, Rautahat, and Janakpur municipalities have issued separate notices requesting people to avoid any sort of animal slaughtering, consumption of meat, fish, or alcohol and instead commemorate the day with lights and celebration. Janaki Mandir Guthi had even demanded the Madhesh government to declare a holiday in the province on January 22. Although the Madhesh Province seems to have declined the request, some local governments such as Shuddhodhan rural municipality and Krishna Nagar municipality of Kapilvastu have given public holiday on the day of Ram Mandir’s inauguration. In short, the grandiose of the temple’s consecration has spilled across the border rather astoundingly, which has some crucial socio-political implications for Nepal.

Ayodhya: A Confluence of Politics and Religion

Before discussing its implications for Nepal, the significance of the (re)construction of the Ram Mandir in India merits discussion. In 1992, Hindu mobs demolished the Babri mosque “claiming it was built by Muslim invaders on the ruins of a Ram temple.” After a long dispute, in 2019, India’s Supreme Court decided in the Hindus’ favor and allowed the construction of a Ram temple on the disputed site. It was a massive victory for the country’s Hindu nationalists and most importantly prime minister Modi, who had rallied for the temple’s reconstruction in his election campaigns.

After a decade since his first election, where he had promised his voters, Modi is set to inaugurate the temple in Ayodhya. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), right-wing politicians, Hindu-nationalist leaders and groups, and Modi himself have all tried to milk the maximum amount of political dividend from the event. In the preparation for the big day, Modi has been following a strict ritual of 11-day Anusthan, where he is “sleeping on the floor and is drinking only coconut water.” While his exceptional PR team converts his religious image to a political message on social media, others have amplified it in their own ways. For instance, India’s defense minister Rajnath Singh has claimed that the temple being rebuilt in Ayodhya is “a symbol of restoration of Indian culture.” Similarly, Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP)’s spokesperson, Sharad Sharma, terms Ram Mandir as “our Vatican City, the holiest site for Hindus across the world.” In portraying the historical event as a victory for all Hindus, they are not only endorsing its chieftain Modi for the upcoming general election but also cementing Hindu nationalism in India to a great extent.

Notwithstanding the religious significance of Ayodhya or a Ram temple in the city, it does not take much to understand that the event is largely a political act. Modi seems to have rushed the temple’s inauguration, which is still under construction. Several priests have boycotted the event “on the grounds that consecrating an unfinished temple undermines scripture.” Modi’s motivation to inaugurate the temple only months before the general election is clear: not only will it reinforce his image as the prime defendant of Hinduism in India, who ‘reclaimed’ Hindus’ glorious past, but it will also send a strong message of his commitment to delivering what he promises. Slogans such as ‘Modi hai toh mumkin hai’ will gain a renewed relevance and prominence in his upcoming campaigns, while other concerns will likely take a back seat. The opposition Indian National Congress (INC), who have boycotted the event accusing the BJP of politicizing it for votes, have only alienated its voters—to Modi’s benefit.

Implications for Nepal

Whether religious or political, the historic day in Ayodhya has some important implications for Nepal. First of all, the actions and behaviors of the public and local governments across the border in Southern Nepal exposes some fundamental realities of the Nepali state and society. The penetration and influence of Modi’s Hindu nationalist politics in Nepal, and particularly Madhesh, is quite apparent. This happens both directly and indirectly—directly through the action of right-wing groups such as HSS and VHP and indirectly through a more gradual and indirect socialization by Indian media and pop-culture. However, the underlying fact that nurtures such ideologies is Nepal’s incomplete nation building or a weak sense of imagined community, to which all Nepalis can share allegiance and loyalty with equal pride. While Nepalis celebrate Poush 27 as the “Unity Day” to commemorate the birthday of Prithvi Narayan Shah, who is credited for Nepal’s territorial unification, we seem to be immune to the fact that a large majority of Hindu Madhesi’s loyalty lies with Modi’s Hindu nationalist ideology across the border.

This fundamental reality, coupled with the apparent jubilation in Madhesh, in days leading up to Ram Mandir’s inauguration further exposes Nepal’s vulnerability in the future. An emboldened Hindu supremacy across the border is likely to encourage similar aspirations in Nepal, albeit led by right-wing groups. This will further polarize the Nepali society, where Muslim and other non-Hindu minorities will increasingly be targets of religious extremism and disharmony. Such developments will push the country towards religious conflicts and communal violence. Nepal avoided such incidents in towns across the border only months ago. Therefore, although the growing religious sentiments may appear to be a political opportunity for Nepali leaders and parties, they should tread with caution.

On whether to offer a donation to my cousins, I had to take caution, too. I had to delicately balance my cynicism for the January 22 celebrations with my mother’s reverence to anything religious and not disappoint her by letting her expectations down. Balancing their temptation to capitalize on the growing religious sentiments with their implications on Nepali state and society may not be that easy for the political parties and leaders in the days to come.

You May Like This

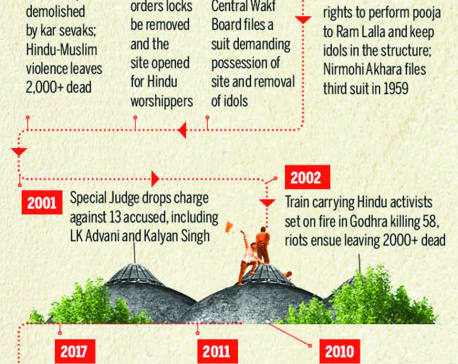

Infographics: The Ayodhya dispute in timeline

The Ayodhya dispute in timeline ... Read More...

Trishul turns Dang temple into tourist spot

DANG: The world’s largest Trishul installed at Ghorai’s Pandeshwor Mandir has been attracting tourists in droves. The trident, weighing 81... Read More...

Hotel Temple Inn begins operation

KATHMANDU, July 12: Hotel Temple Inn has started operation of its service from Sunday. ... Read More...

Just In

- Nepal and Vietnam could collaborate in promotion of agriculture and tourism business: DPM Shrestha

- Govt urges entrepreneurs to invest in IT sector to reap maximum benefits

- Chinese company Xiamen investing Rs 3 billion in assembling plant of electric vehicles in Nepal

- NEPSE inches up 0.07 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.95 billion

- Gandaki Province reports cases of forest fire at 467 locations

- Home ministry introduces online pass system to enter Singha Durbar

- MoLESS launches ‘Shramadhan Call Center’ to promptly address labor and employment issues

- Biratnagar High Court orders Krishna Das Giri to appear before court within one month in disciple rape case

Leave A Comment